Collateral Damage. A Civilian Internee in the Ottoman Empire.

Caroline Adams

Collateral damage is a difficult subject. We can be tempted to brush it off as an unavoidable consequence of war, because by looking at it in its entirety, we are overwhelmed by the amount of human misery it causes. Thinking about the experiences of one person, though, can make it easier to understand what it means to be part of collateral damage. This is the story of one person, Gladys Levack, and of her family and community.

As the base for the British Salonika Force, Thessaloniki housed 18 military hospitals to support a campaign where disease caused much more devastation than the fighting. This aggregation of hospitals necessitated adjacent cemeteries and there are three CWGC cemeteries in the city, with 3816 Commonwealth and 193 other nationality burials from WW1. Most of these are military or nursing personnel but here and there is the grave of a civilian. One of these is grave 1004 in Mikra Cemetery, Kalamaria. It bears the brief inscription:

MISS G. M. LEVACK

16TH DECEMBER 1918

and the register notes:

“LEVACK, Miss G. M. Civ. Ex. Prisoners of War, Turkey. 16th Dec, 1918. 1004.”

Who was Miss G. M. Levack? Why was she in Turkey? The archives give tantalising glimpses, facts without personality, but by piecing them together a dim picture emerges of the woman who is buried there and the type of life she must have led.

Gladys Murray Levack was born in the first quarter of 1881, in Guildford, Surrey and baptised on 27th May, 1881 in St Mary's Church, Guildford. She was the youngest of the six children of John and Jane S. Levack. Her parents were from Scotland, and married in Jedburgh, Roxburghshire, in 1869 but by the 1871 census, they were living in Cheetham, Lancashire. John is described as a 'reader for the press newspaper', presumably a proof reader. Their first two daughters Lisette and Marguerite were born in Cheetham but by the time their third, Helena, was born in 1874, they were in Guildford and Evelyn, James and Gladys were subsequently born there also. John remained in the same line of business, described as a 'printer (reader)' in the 1881 census.

John appears to have been both educated and enterprising, prepared to move around to improve the prospects for himself and his family, working his way from his native Scotland, via industrial Cheetham to Guildford. Records suggest his children were equally industrious. Evelyn was described as a 'pupil teacher' in 1891. She married in 1900. In the 1901 census, the others were living as boarders and all were gainfully employed. Marguerite was in Streatham, working as a photographer, Helena was in Harrogate as a bookkeeper, James was in St Pancras as a merchant's clerk and Gladys was in Lambeth as a draper's assistant. In view of his later international career, it is interesting that James' fellow boarders included nationals of USA, Germany, Persia, Austria-Hungary, Mexico and Jamaica. London was a cosmopolitan city.

Gladys’ father appears to have died sometime around 1904, and by the 1911 census, she and her mother were living with her sister Helena, in the village of Pannal, near Harrogate. Both sisters are recorded as five years younger than their real age and no occupation is recorded for either. Both these facts seem rather odd. Helena and Gladys had both been in employment on the previous census and, like their siblings, living away from home. It looks rather as if their mother had decided they should join her in genteel “penny pinching”, tucked away in a small village.

But brother James had other ideas. Two years later, he and his new wife, Nora, came home to visit the family. Nora was the daughter of Frederick Parry, manager of Lynch Brothers’ Baghdad office. On 10th November, 1913, Gladys accompanied James and Nora on board the “Locksley Hall”, bound for Baghdad.

But why were they heading for Baghdad? This was the era when Britannia ruled the waves. Not only did Britain have an empire but she also exerted considerable political and economic muscle around the world. There were, in fact, many thousands of Europeans living and working in the Ottoman Empire, some of whom had been there for several generations and had never visited their 'native' country. Their commercial and civic lives were governed by 'Capitulations'. Capitulatory privileges were granted by the Sultan to individual nations and generally included:

- freedom to travel to all parts of the Ottoman Empire

- freedom of religion

- freedom to trade according to their own laws with no taxes other than

customs duty, which would be at a fixed rate, agreed bilaterally, and

- exemption from the Ottoman judicial system. Europeans remained

subject to the laws of their own country, administered through courts set up by their Consuls.

The capitulatory system in this form started in the sixteenth century, when the Ottoman Empire was militarily strong and needed to attract European trade but by the nineteenth century it had allowed Europe to dominate trade and industry within the Empire, contributing to its increasing economic weakness. Europe exerted considerable control over the Ottoman economy. The so called Imperial Ottoman Bank was, in fact, financed by European business men and investors, mainly French, but also some British. The Administration of the Ottoman Public Debt controlled about one third of the Ottoman economy and was run by a management board consisting of a representative from each of the seven nations whose private citizens invested in it. Its aim was to provide finance for infrastructure projects eg railways. This was not, of course, a philanthropic process. Its aim was to provide finance for projects which European companies would then undertake, so creaming off the profits to Europe, along with the interest on the loans.

James Levack had worked for Blockey and Cree, Merchants, Baghdad since 1901, after graduating from University College, London where he had studied French, German and Arabic. Around 1913 he moved to David Sassoon's. This was an international trading company that had been set up by David Sassoon who belonged to an eminent Jewish family in Baghdad and who was the grandfather of WW1 officer and poet, Siegfried Sassoon. In addition, James served as honorary American vice consul for Baghdad and was listed as a Director at Large for the American Chamber of Commerce for the Levant. He was therefore a prominent member of the European community in the city. The plan may have been for Gladys to assist her much younger sister-in-law with the social duties which James’ position would have entailed, but the family may also have seen marriage opportunities for her within the predominantly male expatriate group. On the passenger list, she claimed 28 years rather than her real age of 32!

The Levacks would have arrived in Basra in mid-December, 1913. It was not an inspiring place, especially at that time of year! Surrounded by swamps, it would have been particularly wet with the winter floods. Ocean-going ships like the Loxley Hall could not moor at the quay and passengers and cargo were ferried ashore in small boats. Basra would soon be left behind, however, as they continued up the Tigris. Most likely they would have travelled on one of Lynch Brothers’ steamers. Lynch Brothers was a trading company set up by Thomas and Henry Lynch in the early 19th century. Originally from Co Mayo, they were educated, astute businessmen and diplomats, highly regarded in both London and Constantinople. Henry spoke Arabic and Persian, Thomas became Consul General for Persia in London and both were awarded the order of the Lion and the Sun by the Ottoman Empire. By the 1860s, Lynch Brothers also ran the Euphrates and Tigris Steam Navigation Company. Their steam ships were armour plated because of regular gunfire from the local Arab tribes, who disliked all outside interference, be it European or Ottoman. This four-day river journey would finally bring Gladys to her destination, Baghdad.

It is likely that, at this time, British merchants had a very good life in the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman wars in Libya and the Balkans would have had little impact on Europeans, protected as they were by the capitulations. Baghdad was a fine city, on the bank of the Tigris. Although there could be flooding in bad years, this was much less of a problem than in Basra. While summers were hot (110F or more), it was a dry heat and up-market houses were designed with a serdab, a half underground room with wide 'chimneys' leading to the roof and angled to catch the prevailing winds. These were remarkably effective in keeping the room relatively comfortable in the hottest part of the day. The British community probably numbered around 50 – 60 adults, plus some young children; older children would be sent to boarding school in Britain. The British Residency was an impressive building with a beautiful garden running down to the Tigris.

Things would change, however, from mid-1914.

The three Young Turk leaders of the Ottoman government, Enver, Talat and Cemal, negotiated with both sides during the July Crisis to decide who could best support them from their main threat, Russia. On 1st August, 1914, they declared full military mobilisation and on 2nd August signed a secret treaty with Germany. Their problem now, however, was money. The Empire was already economically weak and after the declaration of mobilisation, European banks started to recall loans. This was followed by a run on the banks which caused the government to introduce a moratorium on banking transactions that in due course paralysed the banking system and the overall economy. Closure of the Bosphorus and Dardanelles to commercial shipping had a disastrous effect on trade.

German loans and large quantities of military equipment helped but more money had to be raised. On 9th September, the Ottoman Empire unilaterally abolished the capitulations. Foreign residents now became subject to the same rules as Ottoman citizens, so individuals and businesses could be taxed and livestock, goods and food requisitioned. In Syria, Singer sewing machines were seized to equip the local military uniform factory. In Adana and Baghdad, the Standard Oil Company 'provided' hundreds of cases of kerosene. 'Voluntary contributions' were extracted from individuals and businesses. Taxes were massively increased on non-essential goods like tea, coffee, cigarettes and alcohol. In addition, all foreign nationals were now subject to the Ottoman judicial system, with the consequent risk of spending time in Ottoman prisons, which had a very unsanitary reputation.

The predictable commercial world that the Levacks had entered was falling apart and their privileged position had evaporated. What would Gladys’ life be like as an enemy alien in a society so foreign to someone brought up in late Victorian England? It is clear that the Ottoman authorities could be unpredictable and capricious and life for Europeans was at best insecure. The American ambassador, Henry Morgenthau, and his staff immediately took on the responsibility for consular services for the French and British. Morgenthau took this responsibility seriously, negotiating the repatriation of the British and French ambassadors and their staff and two train loads of British and French citizens from Constantinople. This left several thousand British and French throughout the empire, however, and he and his consular staff intervened in various crises involving civilian internees in Gallipoli, Alexandretta and elsewhere.

The Ottomans generally did not have large concentration camps for their PoWs and internees, instead using vacant buildings and houses in towns and cities. Commercial buildings would have been vacant because of the economic collapse throughout the Empire. Homes were left empty after the deportation of Armenians. In either case, the source of their accommodation would have added to the anxiety and insecurity of those interned. Intermittent imprisonments and threats of reprisal shootings would have kept the level of tension high. As the war progressed, food became scarce throughout the Empire affecting Ottomans and aliens alike. One report suggests prices had increased sixteen-fold between 1914 and 1917.

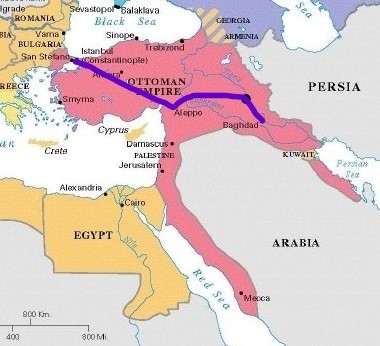

But what was happening to Gladys and her family in Baghdad? On 30th October, 1914, the Goeben and the Breslau, under Ottoman flag but still with their German captains and crew, fired on the Russian fleet in the Black Sea. On 2nd November, first Russia and then Britain and France declared war on the Ottoman Empire. In Baghdad, that afternoon, a force of soldiers and police entered the courtyard of the British Residency. Medical supplies and the old rifles stored in the cellars were confiscated and the treasury strong room and various storerooms were sealed. The Residency’s Sepoy Guard was taken off to the Ottoman barracks. The staff were initially confined to the Residency, then allowed some limited freedom, then confined again and gradually joined by the British vice consul from Kerbala and the British and French businessmen from Baghdad. On 10th December, 1914, they were told to be ready to leave in 2 hours. Thanks to intervention from the American consul, Mr Brissel, they were then given 3 days to prepare. This allowed them to obtain carriages for transport and food supplies. On 13th December, 1914, 11 Residency staff and servants, 26 British businessmen and engineers, one missionary and three French business men, 41 men in all, left Baghdad under Ottoman guard. The Residency staff were to leave the country, the rest were to be interned in Aleppo. A detailed description of the journey is included in the India Office papers available on line in the Qatar Digital Library. It was a difficult journey with threats from the communities they passed through, pushing carriages up mountain tracks and diversions because of fighting in the vicinity. It took the Residency staff two months to reach the port of Mersin from where they sailed for Bombay.

Gladys and her family, however, were still in Baghdad. Presumably due to his position as American vice consul, James was not deported. In addition, Mr Walker of Lynch Brothers was allowed to stay. This may have been because Lynch’s had a contract to transport material for the German funded Berlin-Baghdad railway and this railway was important to the Ottoman war effort. Left in Baghdad, then, were James Levack and Mr Walker, two British gentlemen too ill to make the journey to Aleppo, at least nine British women and 11 children and about 2,500 Indians who, under the Empire, were also British.

Conditions in Baghdad went from bad to worse. Unusually severe floods in December, 1914 destroyed many buildings, leaving many thousands homeless and in early 1915 there was an epidemic of bubonic plague. At its height in January and February, this was killing 40-50 people per week in the city. Outbreaks of cholera also occurred and a plague of locusts in Greater Syria caused widespread famine. For Gladys and her community, simply surviving day to day would have been a challenge. The American embassy and consulates throughout the Ottoman Empire had taken on responsibility for the British and French as soon as war was declared and James would have been kept busy there. Perhaps Gladys, too, helped with the administration. The Indian community was particularly harassed and in need of help. Most were Moslem, and the Ottomans expected them to join the Ottoman forces, especially after the declaration of jihad. In addition, they were taxed heavily. Even if they were allowed to leave the country, few had anywhere to go. Most had arrived as large extended family groups several generations ago and had no land, family or friends in India. The British government did manage to send money via the American consulate to help them survive.

Despite the privations, the British interned in Baghdad did not forget their responsibilities to the wider war. In late May 1915, two escaped and made their way to the British troops, the Indian Expeditionary Force (IEF), who were by this time making their way up the Tigris from their base in Basra. They took information on Ottoman troop deployments with them, as well as news of those they had left in internment.

By early June 1915, the IEF had reached Amara and had, in addition to Ottoman PoWs, captured 50 Ottoman civilian officials. The latter were an encumbrance they could do without, and General Nixon requested permission to exchange them for the Sepoy guard from the Baghdad Residency and the British women and children still in Baghdad. Had this been agreed straight away, it would have been an ideal solution but the Ottomans refused because of the inclusion of the Sepoys in the deal. For the next two years, letters continued to be exchanged on this subject between the Ottoman government and the British government in both India and London. First one side and then the other disagreed to some part of the proposals. It appears the exchange never occurred. It has, however, left a record of what happened to the British women and children.

A further source of information is letters in the National Archives to and from Nora’s father, Mr F W Parry, by then managing director of Lynch Brothers’ head office in London. There are also records of payments which he managed to make to both James and Mr Walker. In January, 1916, he read a letter in ‘Near East’ Journal, stating:

'Mr, Mrs and Miss Levack, Mr and Mrs Walker and two children left Baghdad on November 7th in the direction of Mosul, their destination being unknown. Neither is it known whether they left of their own free will or were exiled.'

He promptly wrote to the Under Secretary for Foreign Affairs asking for further information.

From the available information, all remaining British had been deported from Baghdad by late November, 1915. This is not surprising as there was a build-up of Ottoman troops there as the IEF approached and a battle for Baghdad was expected. (The battle of Ctesipon was fought on 22nd – 25th November, 1915 just outside the city.) The Ottomans did not wish to risk further British escapes from the city and, besides, the women were useful bargaining pawns.

From the India Office papers, it is clear the British authorities had difficulty keeping track of the British internees once they left Baghdad. They appear to have travelled at different times. In addition, five of the women were only British by marriage and several seem to have returned to Baghdad, presumably because they had family there. It appears, however, that Gladys, James and Nora and Mr and Mrs Walker plus two children left Baghdad on 7th November, 1915. They were in Mosul in March, 1916 and Aleppo in September, 1916. They arrived in Constantinople on or around 6th October, 1916, a full 11 months after leaving Baghdad. Nora was five months pregnant when they left Baghdad and Betty Levack was born in Mosul on 14th March, 1914. Her brother, Laurence, was born in Constantinople on 17th July, 1918.

Gladys’ Journey

The journey was across desert tracks and mountains. How did they travel? It is likely that much was done on foot or at best on mules. The British Residency staff had had difficulty obtaining carriages or carts in December, 1914. It is unlikely that there was much wheeled transport available for civilian use by late 1915. Certainly, as Armenians, Greeks and PoWs discovered to their cost, the Ottomans had no compunction about marching their prisoners till they dropped from exhaustion. It is not impossible that Gladys and her companions came across the remnants of the Armenian death marches, as they were also kept for a time in Aleppo. So there was Gladys, in her mid-30s, brought up in middle class, Victorian Guildford, forced to travel around 1,500 miles through hostile country, uncertain of her destination or her fate, uncertain even where the next meal would come from in an empire where even the government troops went hungry much of the time. And sharing her plight, her sister-in-law, pregnant on the first leg of the journey and then with a small baby, three other adults and two young children.

But at last they reached Constantinople and some possibility of news from home in England. A letter dated 5th December, 1916 is from the American Embassy in Constantinople to the American Embassy in London. 'Mr Levack, one of the British subjects deported from Baghdad who has recently arrived in Constantinople' had requested the Embassy to forward some photographs to Mrs J S Levack, presumably his mother, and Mr Parry of Lynch Brothers, Nora’s father. Death records show, however, that Mrs Levack and her daughter Evelyn had both died in Scarborough during the second quarter of 1915. This information appears to have only reached James and Gladys after the photographs had been sent. A second letter dated 15th December, 1916 asks that James' relatives in England be told that 'his family here are greatly grieved at the news' but that they were in good health. This message went from the American Embassy in Constantinople to the American Embassy in London, then to the office of the British Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs who passed it to the Prisoners of War Department. On 17th January, 1917, a month after the message was written in Constantinople, it was sent to Mr Parry to forward to the Levack family in England. The photographs had an even more convoluted journey as they had to be passed by the Chief Postal Censor before being sent to Mr Parry five days after the message. The National Archives contain numerous other examples of enquiries and family information being sent through this route and also record money sent to internees. After America entered the war in 1917, the Netherlands took over the role of providing consular services to interned subjects of Britain, France, Serbia, Italy and America. Communication between internees and their families may have been slow and complex, but at least it was possible.

There is no information on how Gladys spent the next two years in Constantinople or on her hopes and fears as rumours of victories and defeats filtered around the interned community. We can be sure, however, that conditions were not good. It is well documented that Ottoman treatment of PoWs often fell well below accepted international standards, with inadequate food, clothes and housing. In some places, PoWs were used as slave labour. Attempts at aid by charitable organisations such as the Red Cross/Crescent and the YMCA were generally thwarted by the Ottoman government. Although there is little documented about Ottoman treatment of civilian internees, it is unlikely to have been much better. At least in Constantinople, though, the Levacks were in a position to benefit from the small amount of aid that was available through the Dutch embassy and the NGOs. And James and Nora’s two babies survived.

On 30th September, 1918, Bulgaria capitulated. There was now no direct land route for German supplies to reach the Ottomans and it became increasingly difficult for them to continue their war. It ended with the Armistice of Mudros on 30th October, 1918. By mid-November, PoWs and internees were starting to be shipped back to Britain. What happened to Gladys? The only documentary evidence is the record of her death on the 16th December, 1918, in the grave record book in Mikra Cemetery. It can be assumed that either the family were travelling back to Britain via Thessaloniki or that she was already ill when British subjects were being repatriated, and was transferred to the nearest British military hospital. Her cause of death is not recorded but the soldiers on each side of her had both died of pneumonia on the same day. It is possible all three deaths were a complication of influenza as this was during the pandemic. Her time as an internee must have weakened her health. Mrs Walker, who had left Baghdad with the Levacks, had already died in Constantinople in 1916. At the very least, Gladys' life since mid-1914 had been difficult and stressful, with a year of deportation around the Empire, all the insecurity of life as an internee, and the food shortages. It would be surprising if her health had not been affected.

James, Nora and the children survived. James returned to Baghdad after the war as manager of David Sassoon's. Major Pearman of the Army Audit Staff recorded visiting him in 1921 and described him as a 'most cultured and widely travelled man.' He lived to almost 90 and died in Sutton, Surrey in 1968. Nora died 7 years later.

But for Gladys, her travels ended, age 37, in Mikra Cemetery in northern Greece. She had arrived in Basra in 1913 with a position in society and, no doubt, with plans and ambitions. Less than a year later, these had disintegrated, and her fate is a reminder of the collateral damage of any war.

References:

Ancestry.co.uk

J B Angell, The Turkish Capitulations

Hanna Batatu, The Old Social Classes and the Revolutionary Movements of Iraq

Gertrude Bell, Diaries (https://research.ncl.ac.uk/gertrudebell/)

CWGC Website

Ebubekir Ceylon, The Ottoman Origins of Modern Iraq

Familysearch.org

Findmypast.co.uk

The Geographical Journal, March 1913

Grandpa's Journal. mespot.co.uk

J M Hammond, Battle in Iraq: Letters and Diaries of the First World War

India Office Papers, Qatar Digital Library

Paul Knight, The British Army in Mesopotamia, 1914-1918

The Levant Trade Review, June Quarter 1915

Henry Morganthau, Ambassador Morganthau's Story

International Encyclopaedia of the First World War, 1914 1918 Online

National Archives, UK

National Archives, USA

Jeremy Noakes, Intelligence and International Relations 1900-1945

PoliticalGraveyard.com

Qatar Digital Library File 94/1915 Part 1

Eugene Rogan, The Fall of the Ottomans

The Spectator Archives, 22nd January 1910

Kenneth Steuer, Pursuit of an 'Unparalleled Opportunity'

Alan Wakefield & Simon Moody, Under the Devil's Eye