The Dragon’s Voice

In this edition, we have articles by Steve and Nancy, on Bethune town CWGC cemetery, Keith on military history musings, and a review of a book which ponders the question of why WWI did not end sooner.

Bethune Town Cemetery

Steve and Nancy Binks

The cemetery histories available on the CWGC website are copies of the information contained in the cemetery registers. Many have not been updated since they were first produced in the 1920’s. Combining our visits “on the ground” with later research, I have amassed a huge amount of data and information on the cemeteries that we have visited. Although this work is ongoing, here is my first abridged attempt to consolidate this research as an article for publication...(more to follow?)

Bethune was first occupied by the British when Smith – Dorrien’s 2nd Corps (3rd & 5th Division) relieved French units on the 9th October 1914. The earliest British burials made in the cemetery were from the battalions of these two divisions during the Battle of La Bassee (10th October – 2nd November 1914), when the 15th Field Ambulance (FA) of the 5th Division established their main dressing station (MDS) in the town. After that, Bethune became the main site for a division’s MDS holding the Festubert – Givenchy sector(s), and from May 1915, the Hohenzollern sector. Although not exclusive, Bethune was consistently held by First Corps divisions, with the town also used as Divisional, brigade and battalion HQ and as main billeting centre. (This includes Montmorency Barracks, on the current site of Ecole Sevigne).

Although clearing hospitals1 were established in Bethune from the end of October 1914, by early January 1915 they had been moved due to the close proximity of the front line (7.5 kilometres) and the constant danger of hostile artillery. It wasn’t until 28th September 1915, after the opening stages of the Battle of Loos (25th September - 13th October 1915) that the 33rd Casualty Clearing Station arrived in Bethune and was established at St. Vaast College (originally rue de Lillers, renamed Rue Paul Doumer2). It was established as a specialist hospital for “abdominal and other severe cases, unfit to be moved”.

During major operations Bethune was capable of accommodating 4,000 casualties, with six FAs established in the town during the Battle of Festubert (15th - 25th May 1915). During the Battle of Loos, number 5 and number 6 FA (2nd Division) acted as casualty clearing stations (CCS). Trains evacuated casualties to Rouen, Le Treport, Versailles and Etaples. Barges (Number 2 Ambulance Flotilla) also operated, taking casualties to St. Omer, a journey of ten and half hours.

1 Later retitled Casualty Clearing Station (CCS).

2 Paul Doumer was a French president who was elected in 1931 and assassinated in 1932.

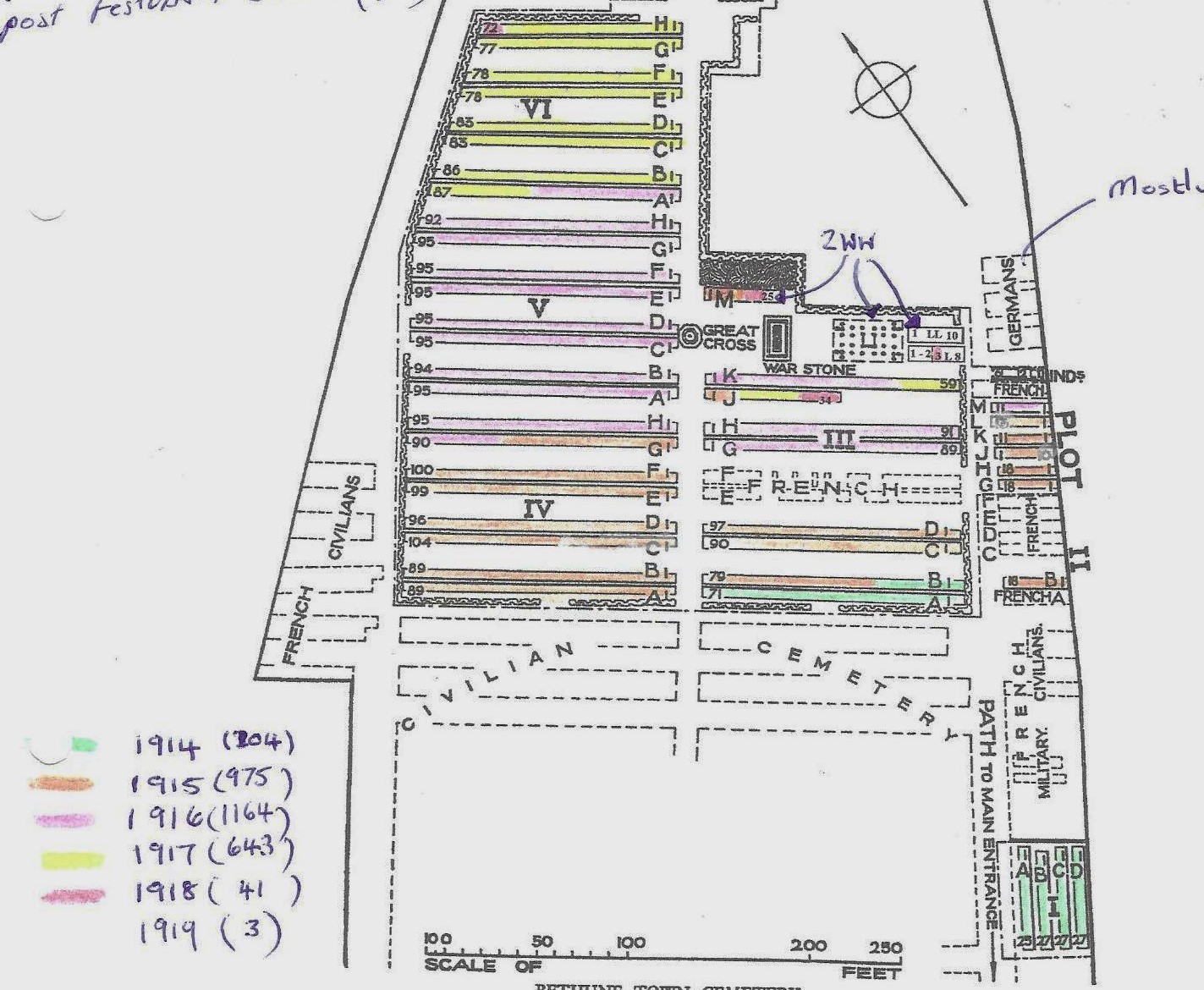

Here is a breakdown of the burials by year and key actions:

1914 204 (Battle of La Bassee)

1915 975 (Battle of Festubert, Battle of Loos)

1916 1164 (German gas attacks, fighting for the Hohenzollern Craters)

1917 643

1918 41 (Battle of the Lys, no burials of 55th Division holding Givenchy sector)

1919 3

The 33rd CCS moved from Bethune at the end of December 1917 and was not replaced; it had become a quiet sector in the later part of 1916, with no burials through the period December 1917 to September 1918.

Cemetery Layout (See plan below)

The earliest burials (now plot 1) were made within the civilian cemetery, but in a British military plot. With a shortage of space, burials then continued beyond the cemeteries north eastern boundary; firstly into what became plot 3. (Plot 2 became an officers’ plot after). After that, burials continued sequentially through plots 4, 5 and 6.

Unusually but not exclusively, the graves are laid out back to back and likely that these are not individual graves, but trench graves, confirmed through the lack of absolute date order, and same date of death in more than one row. (Again, this indicates the lack of exclusive control of the burials by just one medical establishment. Field Ambulance units were scattered across Bethune.)

Notable Burials

There are 3004 British and Commonwealth burials (plus a small French, German and WW2 plot), eleven of which are unknown. There are only a handful of Indian graves3, even though the Indian Corps held the Bethune sector (October – December 1914), although British battalions of the Indian Corps and their officers are buried at Bethune. There are 57 Canadian burials, mainly First Division (from the Battle of Festubert). There are no ANZAC burials.

It was here at Bethune Town Cemetery in late October 1914 that Colonel Edward Stewart, a Red Cross inspector, met with Fabian Ware and passed comment about the danger of losing the inscription detail on the makeshift crosses. From that moment, Ware’s mobile unit took responsibility for registering the graves of the fallen, which eventually led to the forming of the Graves Registration Commission; the forerunner for the Imperial War Graves Commission (May 1917).

3 Hindu Indian troops would most likely have been cremated, according to the requirements of their religion.

It was probably the graves in what is now plot 1, as they date from October 1914, although row A extends in to 1915 as officer burials and include the grave of Victoria Cross recipient Lieutenant Frank de Pass, 34th Poona Horse, who fell on the 25th November 1914 whilst attacking a German sap close to Festubert.

In plot 4, row A, in adjoining graves are Lance Corporal William Price and Private Richard Morgan of the 2/Welsh Regiment. They were executed in February 1915 for the murder of Company Sergeant Major Hughie Hayes. At their court martial, they pleaded guilty to murder but explained that they had shot the wrong man! The “wrong man”, is buried in plot 3, row B.

Bethune suffered from occasional bouts of German bombing and air raids, the most destructive of which took place on 28th May 1918 when the town square was flattened. Twenty five percent of the houses and buildings were destroyed, and 28% damaged. Thankfully, medical units had already evacuated Bethune, as the German Lys offensive had brought the front line to within three kilometres!

|

In November 1914, Hindu soldiers were treated here. Several other buildings which were used as billets and medical establishments still remain in Bethune |

On the 7th August 1916, Bethune suffered from a three-hour hostile bombardment including a 15” shell which landed on 33rd CCS, based at St. Vaast College. Two hundred and four patients were evacuated to the cellars by the medical staff whilst two operations continued. Twenty four servicemen were killed, mostly drivers of the Army Service Corps. They are buried side by side in plot 5, row H. Five nurses who were on duty were later awarded Military Medals.

The final military burials made at Bethune Town Cemetery [Photo above] took place on Christmas Eve 1917. At 2.30pm on the 22nd December, the 8th Manchesters completed their relief of the support trenches at Givenchy. The companies marched independently to their billets at Oblinghem. As D coy marched through Bethune enemy air planes dropped around 50 bombs on the town. Four to six fell close to D coy.

The war diary confirms the casualties as: 1 officer and 21 other ranks killed, 1 officer and 7 other ranks died of wounds, 1 officer and 35 other ranks wounded.

So, why did WWI last for such a long time? It was always on a knife edge.

A review of a book by Holger Afflerbach

Verlag CH Beck, Munich, 2018

This is indeed a book review, but given that the book itself is in German and therefore not easily accessible, this review gives a more detailed account than would normally be the case.

Holger Afflerbach is the Professor for European History in the University of Leeds. He is German, and the book is indeed in German – its proper title is Auf Messers Schneide.

In this book, he looks afresh at the conduct of the war, the politics of it all, both national and international, and the state of the home front in Germany. In doing so, he debunks some myths and misconceptions, and provides new insight into the reasons that the war continued for as long as it did.

The book starts with an analysis of pre-war European politics. There was a general belief that in any future war there could not be a victor as such – that a war between the Great Powers would be suicidal for all of them. However, Germany saw itself sandwiched between Russia to the east, and France and Great Britain to the west. There was confidence bordering on arrogance as regards its military capabilities, having defeated Austro-Hungary and then France in the 19th century. The German public had a pride in its armies and faith in the military leadership. All had confidence in the military superiority of their country.

Norman Stone has said that, like all the other armies in Europe, the high command did not comprehend how the impetus in warfare had moved from offence to defence, due to the introduction in the 1880s of ammonium nitrate based explosives, quick-firing artillery such as the French 75mm, and the Maxim-patent machine gun.

The Schlieffen plan was von Moltke’s attempt to knock out France before engaging Russia. Afflerbach points out that it was only in 1912 that General Joffre decided that French war plans should not include invading Belgium and Luxembourg. A French historian has written that France won WWI in 1912, as an invasion of Belgium would have alienated both Great Britain and the USA. In the event, Russia beat everyone to the starting gate, and invaded German territory in East Prussia before any German soldier set foot in Belgium.

Hindenburg was brought out of retirement to nominally lead the campaign in the East. In fact, Ludendorff was the military brain but he had no charm or PR appeal. Hindenburg became the “saviour of Prussia”, as he was given the credit for pushing the Russians out of East Prussia, and a popular figure in Germany as a result. At the end of the war in 1918, as things were collapsing in Germany, Ludendorff was sacked and did a runner to neutral Sweden, disguised as a diplomat.

The myth of the victory at Tannenberg in August 1914 was Hindenburg’s creation. It was, in fact, a late suggestion for the name of the battle, which was actually at Allenstein, some 30kms from the site of the 15th century defeat of the Teutonic Knights, for which it was supposedly vengeance. (One earlier, unmemorable, suggestion for a name had been the Battle near Gilgenburg-Ortelsburg).

The scenario on the home front changed from 1914/15, where there was optimism about a great military victory, to 1917 where the effects of a coal and food shortage lead to the “turnip winter”. This change of mood is well illustrated in the book by contrasting Christmas “selfie” photos of the Wagner family in Berlin in 1915, with plenty of the table, to 1917 where they are wearing overcoats indoors.

Photo above: the Wagner family in Berlin at Christmas 1915. The map behind them shows the Western and Eastern fronts, far into foreign territory. There is a rather immodest display of the family’s possessions including fancy gloves and plenty of food.

Photo below: the same scene at Christmas 1917 with the coal shortage during the “turnip winter”. There is still a pretentious display of their possessions but less impressive than before, with less food on the table, and of course they are wearing their overcoats indoors.

Strikes grew more numerous. In 1915, there were 42,000 strikers but in 1916 this figure grew to 245,000. This is an indication of increasing social unrest and dissatisfaction.

Ultimately, there was increasing unrest by autumn 1918, leading to the November revolution in Germany. Incidentally, the downfall of Kaiser Wilhelm seems to have been almost accidental, as the American view was that he could remain as a monarch in the British mould, with no political power.

The unrestricted U-boat war from 1917 is analysed in the book. It was, in fact, a populist move, much like some of the simplistic policies of US President Trump, or indeed closer to home, that are supposed to solve everything but in reality solve nothing. Those who understood the naval situation were convinced that it could not succeed and they were right: the pressure for the offensive came from the public and the army, not from the navy. The fear was that such a move could bring the USA into the war, which indeed it eventually did. Such a move could paradoxically improve Great Britain’s supply situation, as the USA would go all out to keep Britain supplied.

Professor Afflerbach’s analysis of the figures for the unrestricted U-boat war does cast matters in a more informed light than is often the case. If the tonnage sunk is broken up and expressed per U-Boat or per day of deployment, then the figures for ships sunk are only marginally higher than previously. Indeed, in the Mediterranean the figures were actually lower. The point is that there were more U-boats deployed, not that the tactics made much difference. One of the problems for the U-boats was finding targets. The use of a wolf pack, as happened in WWII, was not feasible, as you need long-range aerial reconnaissance to locate the convoys and transmit that information to the U-boats, which also implies good radio communications. So, in WWI the U-boats had to hang around the shipping lanes, typically the approaches to major ports. For example, the locations of ships sunk by U-boats off the Welsh and Irish coasts are clustered around the ports such as Holyhead and Dun Laoghaire (Kingstown in that era).

The unrestricted U-boat campaign put an end to the peace discussions that had been going on since late 1916. The war positions of the various protagonists were disparate and complex. A very real fear of some in the German leadership was that Russia would disintegrate into chaos of a communist revolution sparked from within, and that would generate mass unrest in Western Europe. The decision, or lack of decisiveness, to let the war continue into 1917 and beyond was to let Europe glide into a catastrophe. The consequences were a dysfunctional post-war order, communist and fascist dictatorships, the “bloodlands” of eastern Europe, a second world war, and the cold war. A compromise peace in late 1916 and early 1917 could thus probably have avoided the subsequent catastrophes of the 20th century.

France and Italy had clear, nationalistic, albeit destructive, war aims. The British war aims were more nebulous. Certainly, both the British and the French had their eyes on new colonies at the expense of the Ottomans, as evidenced by the Sykes-Picot agreement. A central war aim was to put Germany in its place. In other words, the British saw the conflict as a return of the Napoleonic Wars and a struggle to restore the balance of power in Europe. The belief was that could not happen until Germany was defeated, and a negotiated settlement would not do that. The comparison was with the negotiated peace agreement signed in Amiens with Napoleon in 1802, which only lasted a year. However, the continuation of WWI put Britain and France into more debt to the USA and bolstered the USA’s position as a centre of world finance, which continues today. Lord Lansdowne was one voice who sought compromise. On the other hand, the cabinet of Lloyd George saw things as a military issue, not as a political one. Perhaps this was a common failing of British governments throughout the 20th century?

The “victory” which the Entente of 1916 sought was ill-considered goal setting. Neither the collateral damage that was to ensue, ie hundreds of thousands of deaths, was brought into consideration, nor how to bring about a functioning peaceful framework. This only changed with US President Woodrow Wilson’s “peace without victory” and his fourteen points.

This brings us to the key problem of dealing with the Entente – it was a coalition. So, who can you negotiate with? That issue was only resolved in 1918 when the USA came into the war openly, and President Wilson was seen as the man in charge. However, the Kaiser Schlacht offensive of March 1918 was a major obstacle to negotiations at that stage. Then, in October 1918 the sinking of the RMS Leinster between Dublin and Holyhead with the loss of 567 lives hardened President Wilson’s position. (My goodness – an historian who has actually mentioned the Leinster). By 1918, of course, Russia was out of the war and in a civil war, with which the Entente were interfering, remarkably unsuccessfully. Communism was seen as the rampant danger which would “infect” the populations of the West.

A key component of Wilson’s plan was self-determination for national groupings. Indeed, one of the suggestions inside the German government earlier on in the war was to allow the population of Alsace and Lorraine to have a vote on which country they wished to belong to. The problem there is that there would have been consequences for other regions, especially Poland. At one stage, the Germans sought to raise a Polish Legion to help fight the Russians, with little success. But, once you have recognised the Poles as a national group how can you not give them a vote on their future? Where would the territory for this new Poland come from? It could not all come from Russia. Austro-Hungary had a large Polish population, predominantly in Western Galicia, which presumably would have to be given up. In Germany, there was a significant Polish population in part of East Prussia, which is where Falkenhayn, Luddendorf and Hindenberg came from. So, could you cede the homeland of your politico-military leadership to form part of a homeland for the Poles? Politically, it was thought unacceptable at the time, but it is part of Poland today, as is Western Galicia.

Another key aspect of WWI is that it was indeed a world war, not just on the Western Front. It was in the Middle East, Eastern Europe, the Caucasus, Asia Minor, the Balkans, and Africa. In short, it was going to be very complex to unwind the military engagements all over the world – who would give up what territory and who would take it over? It was not just a matter of vacating Belgium and deciding what was to happen to Alsace and Lorraine.

It is worth mentioning the issue of the Ottoman Empire, which rather came into the war by the back door. The German High Command (OHL) believed that the Ottoman forces would equate to one percent of the German strength and would need bolstered. (Afflerbach points out the similar undervaluing of the Soviet army by the Allies in WWII, which ultimately pushed the Nazis and their allies out of the Soviet Union and all the way to Berlin.) In the end, the Ottoman army lasted until October 1918 and occupied 1.5 million Entente troops for four years, which was no mean achievement. The author points out the Ottoman view of Gallipoli, which was their first military success in 100 years or so, and which bolstered their morale enormously.

Looking at the strategy of the war, the author refers to two catastrophic political decisions which caused so much death and destruction. The first was not to avoid the war in the first place. He quotes Clausewitz’s dictum that war is the continuation of politics by other means, and indeed Foch said that one wages war only to get the desired result. The second catastrophic decision was to let the war run on so long, but it is much less discussed today. Lord Lansdowne aired this issue in 1917. The Entente are portrayed in other publications as wanting to prevent a German takeover of Europe, but was this a realistic fear? Afflerbach’s point is that the German system of government was deeply flawed, with a monarch as a central figure. The military leadership was a key political force that suffered from arrogance and tunnel vision, and a lack of reality. Germany’s allies, Austro-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria, were even more compromised, with moribund structures, certainly in the case of the first two. However, the Entente increasingly had imperialistic goals as the war progressed, and was less and less looking for an end to the war.

Professor Afflerbach opines that the two strategic mistakes which the German regime made were, firstly, the invasion of Belgium and, secondly, the U-boat war. The invasion of Belgium made it virtually certain that Britain would enter the war on the side of the French. The U-boat war of 1917/18 brought in the Americans as participants when perhaps otherwise they might have remained behind the scenes, possibly pressuring all sides for a political settlement.

So, the old order was destroyed by autumn 1918 and the new order did not function. But it could have been otherwise – it was all on a knife edge. In many ways, the problem for Germany and her allies was how to get out of the mess that they had created in 1914, and indeed they did try to do so, with an absence of success. They were in defensive positions on the Western Front and knew they could not win, especially once the US bolstered France and Britain with finance and supplies, and eventually with soldiers. The various voices in the German regime could not come up with a common position to solve the deadlock, in terms of what to concede, at various stages. As we have seen, the Entente were pushing their own war aims and perhaps would not have agreed to any negotiated settlement, earlier than they did.

Professor Afflerbach’s analysis of the situation is as follows:

The international club of war prolongers lived under a chimera, a concept of “victory”, which they expected to be the solution to the political problems, many of which emerged because of the war, and those existing ones that were aggravated because of it. This is not only an element of WWI but of wars in general and also can be seen in many conflicts of our own time.

The way out of the WWI conflict was open for a long time. It was such a bitter conflict with such wide-reaching consequences for various reasons. For a long time, it was perched “on a knife edge”; it lasted too long; it could have had other endings and both the victors and losers knew that; and the victors ultimately, weakened as they were, in their moral, social and financial misery which the war had generated, could not be other than merciless.

Overall, the book is, dare I say it, not particularly light reading, but is an insightful analysis of the political and strategic situation which castes new light on the spurned possibilities for an earlier end to WWI which would have saved so many lives and so much destruction.

Trevor Adams

Summer Musing

(Part 2)

Keith Walker

Here I am still in lock down, sitting in my corner surrounded by my books musing and looking at some of the things I have collected over the years in connection with the wars.

Many years ago, there was an antique shop, to be honest it was more of a bric-a-brac shop, in York St, Wrexham. This is where I started my first collection of medals and cap badges. I remember picking up WW2 Campaign Stars for 7/6s (37 ½ p) and cap badges for 5s (25p). World War One Trio's were only 10s (50p). Now the prices are off the scale! WW2 Stars are £20 to £200. Cap badges are £40 and upwards. WWI trios are £ 200 plus, depending on which regiment. Two of my cap badges in my collection I did not pay for, a Gordon Highlander [top photo] and a REME [bottom photo], and like everything to do with the war they have a story.

REME (Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers.)

The REME was formed in 1942. It became the Corps of the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers in 2008.

When I started to work in the early 1960s at Brymbo Steel Works, I was working with veterans of WW2 and, like so many veterans, they were reluctant to tell their stories, but two, I call them my two Tommies, did tell me their stories and give me their cap badges, as they had no family to leave them too. The first Tommy H was a local lad born and always lived in the Brymbo area. He was called up and posted to the REME. In civilian life, he was an electrical fitter. After his initial training, he was in a light aid detachment attached to a Royal Artillery light anti-aircraft gun battery who were kitted out with 40mm Bofor A/A guns, towed by Morris C8 Quad tractors. The ammunition was brought up in AEC Matador 10-ton lorries. It was Tommy's job to service the C8 Quads and the lorries. They landed on D-Day at Sword beach. His memory of his time in the war was of the way in which the army adapted. He said as they moved inland from the beaches there was not much enemy air activity so the officer in charge of the Bofor gun alternatively levelled them and together with a RAF ground controller used the gun to mark targets with coloured tracer rounds for the Hawker Typhoon ground attack aircraft to hit with rockets. He said this looked quite spectacular but would not have liked to be on the receiving end. Tommy H served until the end of the war. He was demobbed in 1947 and returned to his job at Brymbo Steel Works, married and lived in Brymbo for the remainder of his life.

Gordon Highlanders

This regiment was formed in 1881 and disbanded in 1994 to be amalgamated with the Queens Own Highlanders (Seaforth and Camerons) to form the Highlanders (Seaforth, Gordons and Camerons). In 2006, they became the Royal Regiment of Scotland.

The Gordon Highlanders 1st Battalion and the 5/7 Battalion were part of the 153th Brigade which was part of the 51st Highland Division. They landed at Sword beach on D-Day. The battalions fought at the Battle of Caen in July 1944, the Battle of the Falaise Gap in August1944, and the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944. My second Tommy M was born and brought up in South Wales. In civilian life he worked as a miner. He met his wife who was from North Wales during the war. They were married in 1946. Tommy M moved up to North Wales and found work at Brymbo Steel Works. He settled in the Wrexham area. Tommy M was badly wounded at the Battle of Caen and was invalided back to the UK. He was shipped from France to South Wales, then entrained up to Scotland to a hospital at Inverness. Tommy M told me he thought it quite funny that he could have waved to his mother from the train in South Wales. She was worried that he was fighting in France while he was actually being transferred to the regimental hospital in Scotland.

When he got to Scotland, he was allowed to send a postcard back to his mother. Tommy M took some time to recover from his wounds and never returned to his regiment, being demobbed in 1946. His overriding memory of his time in the war was the smell and noise. He remembered the smell of cordite from the big guns as they approached the beach in the landing craft and the smell of men being sick and relieving themselves. He said it was the smell of fear. The noise from the bombing and artillery fire at the battle of Caen he said made his whole body shake. The close fighting in the city, he said, was intense. He thought he was shot by a sniper.

Both my two Tommies did not think of themselves as heroes - they were just doing their job. They did not want people to think they were special and were reluctant to tell their stories. Both now have passed away but I still keep their privacy.

World War One Medals

Mons Star, British War Medal, British Victory Medal

Mons Star, British War Medal, British Victory Medal

This is a trio that I picked up a few years ago which had been awarded to Private G. Wilson, Army Service Corps. The Army Service Corps was formed in 1869. It got its royal title in 1918 and became RASC. In 2008, it amalgamated into the Royal Logistic Corps. I have searched on all the databases and cannot find him, which pleases me as I can only assume that he survived the war and hopefully lived a happy life.

Speaking of medals, we are all aware that Queen Victoria was instrumental in the design and presentation of the award of the Victoria Cross. An interesting article in the June / July edition of Medal News caught my attention. Queen Victoria, after receiving criticism of the Crimean War (Oct 1853 - Feb 1856) by the war correspondents and public opinion, called for a hospital “for our sick and wounded soldiers is absolutely necessary and now is the moment to have it built”. Queen Victoria wrote on the 5th March 1855 to Lord Panmure (b April 1801 - d July 1874) Secretary of State for War (8th Feb 1855 - 21st Feb 1858) about creating a hospital.

Plans were approved for a site at Netley on the eastern shore of Southampton water. The site was started in January 1856. The Queen urged Lord Panmure to have the site cleared and ready by May 1856, so that she could lay a foundation stone. At the same time in January 1856 the Queen was in correspondence with Lord Panmure about a new bravery decoration. She sent him drawings of various designs with her preference marked. In March 1856, she sent some actual samples to Lord Panmure and stated she was desirous to have one to keep. She was duly given one.

On May 19th 1856, the Queen was at Netley to lay the foundation stone. She was shown the plans of the hospital. The Queen placed copies of the plans in a copper box along with various coins of the realm, a Crimean War Medal with the four clasps for the Battles of “Alma”, “Balaklava”, “Inkerman” and “Sebastopol”, and a Victoria Cross. The copper box was then placed in the foundation stone of Welsh granite which was lowered into a bed of mortar. There it rested until September 1966 when the building was demolished. Speculation was rife about what was in the copper box.

On December 7th 1966, the great and good of the Army Medical Services gathered, the foundation stone was raised and the copper box recovered. Inside were the plans, coins, Crimean medal and an unnamed Victoria Cross. After much debate, it was decided that the cross be engraved by Hancocks & Co Ltd of London. This was done in January 1967. The engraving reads:

Placed by HM Queen Victoria

In Foundations RVic Hospital Netly

On the reverse centre it states:-

Sited 19 May 1856

Recovered 7 Dec 1966

Is this now the first presentation of a Victoria Cross to the Army Medical Department, as it pre-dates the Hyde Park one by 13 months? Netley is May 9th 1856 and the Hyde Park one is June 26th 1857. As they say in class at university “discuss.” The article in Medal News went on in detail about Queen Victoria's connection with the Netley Hospital. The Crimean medal and the Netley Victoria Cross can be seen at the RAMC Museum, Keogh Barracks, Mytchett, Surrey.

Is this now the first presentation of a Victoria Cross to the Army Medical Department, as it pre-dates the Hyde Park one by 13 months? Netley is May 9th 1856 and the Hyde Park one is June 26th 1857. As they say in class at university “discuss.” The article in Medal News went on in detail about Queen Victoria's connection with the Netley Hospital. The Crimean medal and the Netley Victoria Cross can be seen at the RAMC Museum, Keogh Barracks, Mytchett, Surrey.

So now I will carry on musing in my corner with my books. Philip has introduced me to “the joys of internet shopping” and I have purchased a nine DVD box set by the BBC “World War One, the Centenary Collection”. That should keep me occupied for a few hours. Stay safe!

Acknowledgements and references

Medal News June/July edition

St. Vaast College housed the 33rd CCS from September 1916 until December 1917.

St. Vaast College housed the 33rd CCS from September 1916 until December 1917.