The Dragon’s Voice

In this edition, we have articles by Terry Jackson on the Isle of Man in WWI and an article by Steve and Nancy on the Railway Chateau cemetery in the Ieper area. It is likely that the next issue of this newsletter will February 2021. In the meantime, Merry Christmas and a better New Year than this one has been!

There were will a Zoom talk at 8pm on Friday 11th December when John Crowther will be talking on “Just names on a memorial”. (Strictly speaking, this is for the Lancs and Cheshire branch but obviously anyone can join the talk as it is on the internet). The talk is about the results of research on the 12 names on the memorial plaque in Heswall Methodist church, where John is a lay preacher. Nobody knew anything about these men but a research project for the centenary Remembrance Day service uncovered more than was expected.

The details of how to connect are as follows. You can either click on the link and it will take you through to Zoom and download Zoom software and take you into the meeting, though you will need to enter the passcode when asked. Otherwise, you can download Zoom software and set up your own free account. You then use the meeting ID and then the passcode to enter the meeting. Doors open at 7.45pm! Click on “Join with computer audio” to be able to listen. You can click on “Join with computer video” if you wish to be seen! Login details are:

Time: Dec 11, 2020 07:45 PM

Join Zoom Meeting

https://us02web.zoom.us/j/84275931811?pwd=QnU5UmJ5dEx4dU51dC8xUk1PSG5IUT09

Meeting ID: 842 7593 1811

Passcode: 802440

Railway Chateau Cemetery

Steve and Nancy Binks

We visited Railway Chateau on the 25th July, 2012 as part of our “SomeKindHand” Pilgrimage. It was my second visit; the first was shortly after the grass had been dug up and replaced with gravel. It was selected as one of four cemeteries (in France and Belgium) that the CWGC wanted to use to trial more sustainable gardening practices, due to the impending issue of global warming. A special register was set up in each cemetery and the public were asked for their comments. I did not see one positive entry! Most visitors saw the scheme as a way of cutting back the gardeners and as such the trial was scrapped and the grass reintroduced. Ironic that the headstones behind the Cross of Sacrifice (row C, graves 13 & 14) are those of Private Arron Wason Gardner and Corporal James W. Gardiner!

Wartime Location

The cemetery lies 1350 yards west of the outskirts of Ieper, just north of the main Poperinge to Ieper railway line, on what was possibly Augustijnenstraat (Augustine Street), now Adriaansensweg.

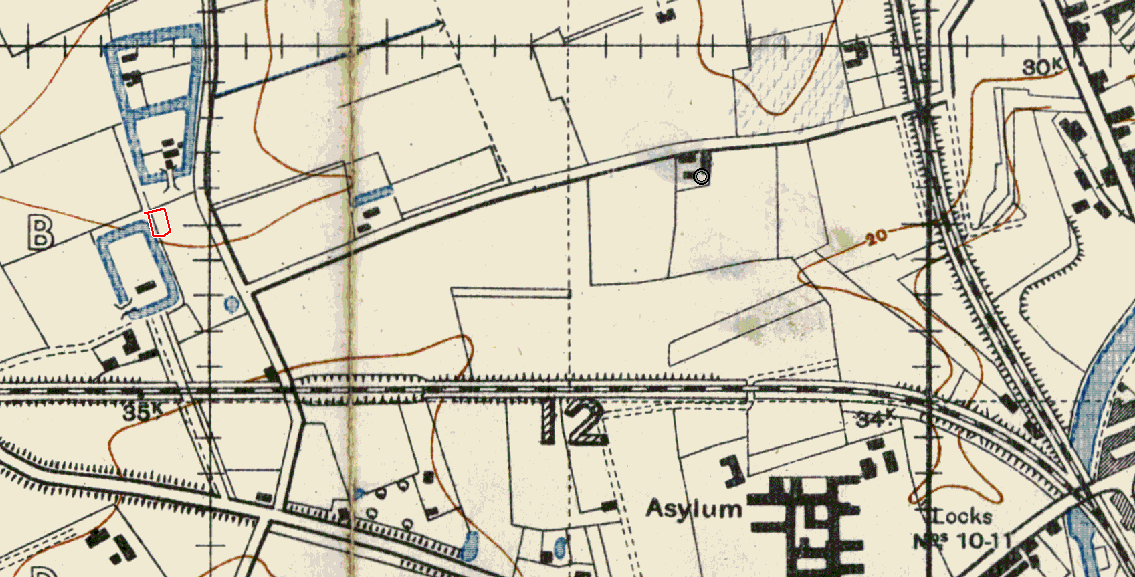

The first cemetery register printed by the IWGC lists the cemetery within Vlamertinghe. A 1918 trench map (using Trenchman Satnav) places the cemetery between (the rear of) Bobstay Castle and (the front of) Crojack Farm, (both nautical terms). Bobstay Castle is likely to have been “Seminariekasteel”, where priests were trained. It was rebuilt in the post war years and is still in existence.

In October 1914, on the arrival of the BEF in Ieper, the cemetery location was 6.2 miles behind the line that was established at the end of the First Battle of Ypres. By April 30th 1918, after the German Lys offensive, the cemetery was 2.5 miles behind the British front line, but now within the British support line. The 4/Worcestershire regiment war diary records: “Battalion headquarters at Bobstay Castle in support lines”.

Location of Railway Chateau Cemetery (red rectangle, half way up the lhs of the map) on a 1917 trench map, north east corner of Seminariekasteel (Bobstay Castle). The 108th Battery was located close to the farm, 1,500 yards east of the cemetery.

Burial Ground Name

The CWGC cemetery history states that Railway Chateau cemetery was also known as St. Augustine Street Cabaret and L.4 Post. In correspondence with Aurel Sercu of Ieper, he suggests that both Railway Chateau and St. Augustine cemeteries are marked on a map in the White Cross Touring Atlas, dated circa 1920.

Cemetery Origins & Chronology

The earliest burials date from the 1st November, 1914, when three men from three different divisions were buried in a collective grave (now C.8). It is highly likely that these were the first burials made by 4th Field Ambulance (FA), tent division, 2nd Division. According to their war diary for 31st October, 1914:

“Dressing station opened at the château [“Seminariekasteel”]1 mile west of Ypres,

200 beds.”

A further diary entry for the 11th November states:

“One officer of London Scottish died during the night, Captain Ker-Gulland”

This officer, 2/Lt. Reginald Glover Ker-Gulland is buried in Railway Chateau Cemetery, row C, grave 9.

Through the period of the 1st - 17th November, 1914, 61 burials were made in just 12 collective graves of what is now row C (graves 5 – 13) and row B (graves 5 - 7). The vast majority of these 61 burials belong to infantry from 1st, 2nd and 7th Divisions.

The usual convention of one FA responsible for each Infantry brigade collapsed during the chaos of the First Battle of Ypres. The Assistant Director Medical Services (ADMS) war diary for 31st October states:

“24 hour admission to 4, 5 and 6 FA’s = 753 British and 9 German. Only 215 belonged to 2nd Division.”

A further diary entry states that the number of burials made at the château (up to 16th November) amounted to 73. If all these deaths resulted in burials immediately in the vicinity of the château, then it begs the question that there may have been another smaller burial ground, whose graves were later exhumed and concentrated elsewhere? Alternatively, any German burials (if included in the above figure) could have been removed? (The war diary confirms the treatment of many wounded enemy soldiers).

When the French took over the Ypres front, BEF units withdrew to refit. The 4th FA left the château on the 17th November 1914 and moved in to billets at Meteren, just over the border. The dressing station was at St. Augustine Cabaret. The château was used by the French until the British returned in April 1915 and made the following burials:

1915 12 burials (including six graves from 108th battery RGA)

1916 6 burials (including four graves from 108th battery RGA)

1917 20 burials (vast majority are labour corps men)

1918 no burials

In May 1915, 108th Heavy Battery, Royal Garrison Artillery (RGA) established the first of two 60 pdrs near Reigersberg, with the ammunition column:

“in a field just off the Elverdinghe – Vlamertinghe road but was shelled during the night and moved to a farm S.E, behind château on a parallel road.”

Over the coming two weeks, the battery buried five men in the cemetery. The war diary for the 11th May records:

“Enemy ranged on battery by aeroplane, Lt. Cottrell killed in action by a piece of shell. Quite irreplaceable. Funeral was conducted by Rev. C. M. Chavasse [Noel’s brother], in a piece of ground railed off as a cemetery, square H.12.a.0.5” (This coordinate is approximately the entrance to the grass entry path of the cemetery.)

The 108th Heavy Battery, RGA, remained in the Salient through 1916, making a further six burials.

The final burials took place in September – October 1917, when after the advance to the Passchendaele Ridge, pioneer and labour companies built a large network of light railways, dumps and billeting camps*. All 20 casualties from 1917 were either men from the labour companies, (particularly 17th Coy), Royal Engineers or Pioneers (12/Koyli (Miners) attached to 5th Army troop). Nine men of the 17th Labour company who fell on the 26th September are buried in a collective grave. The circumstance of their death can only be surmised as probable enemy aircraft, as none of the casualties contain any further detail in their cemetery register entry and no war diary is available.

(*This assumption is based on trench map detail, that shows no defences until after March 1918.)

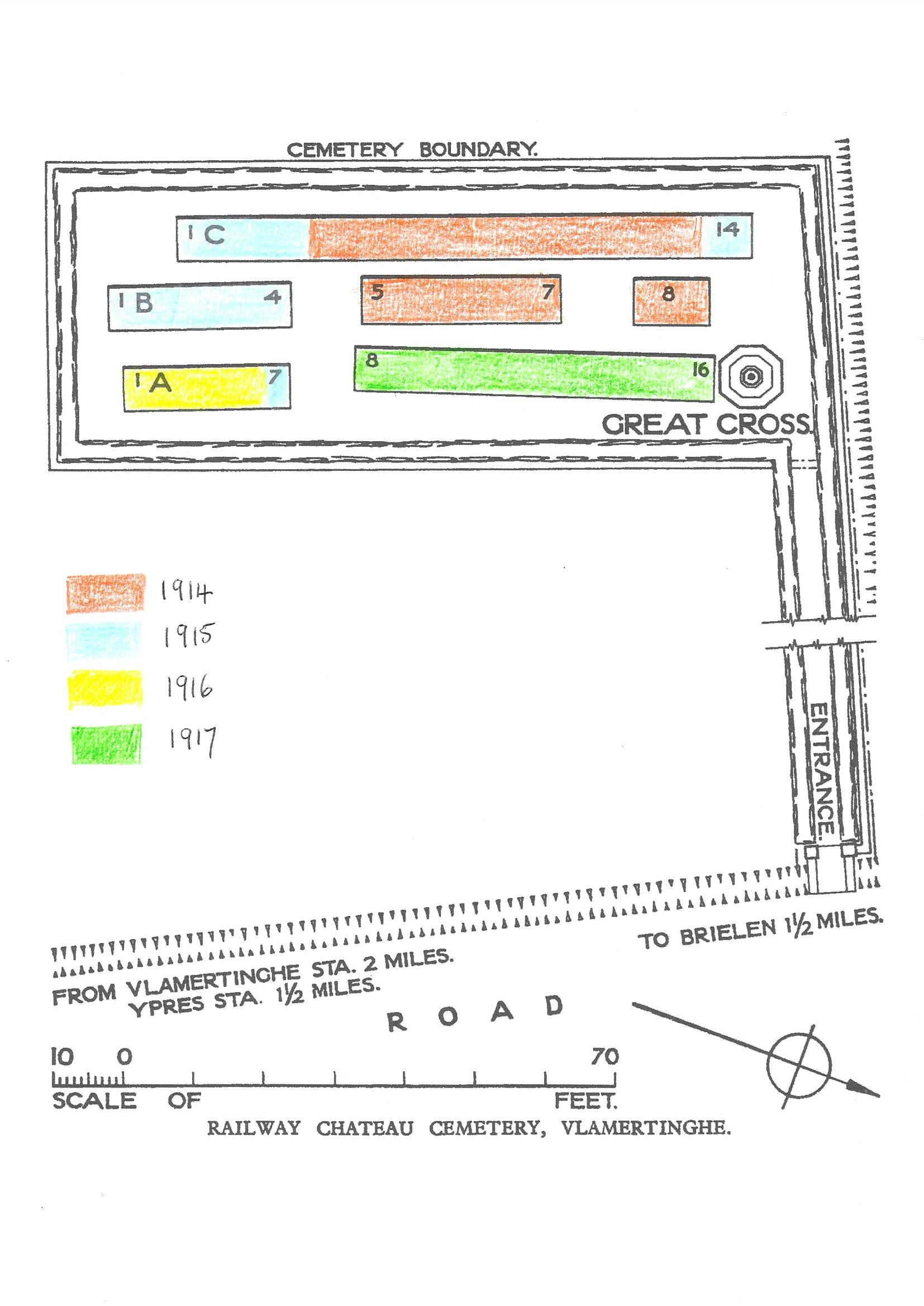

Cemetery Layout (see cemetery layout plan)

The 61 burials from November 1914 were made in collective graves, in what is now row C, graves 5 – 13 inclusive and graves 5,6,7 and 8 of what is now row B. The 12 burials of 1915 extended row C on either side of the 1914 burials and extended row B on its left hand side. One grave was made in what is now row A, grave 7.

The 6 burials of 1916 were made in what is now graves 1 – 6, row A. The 20 burials of 1917 were made in what is now graves 8 – 16 of row A, with grave 16 being a collective grave of 9 burials, (26th September, 1917). According to the original IWGC cemetery register, one French artilleryman’s grave was removed (row B, grave 9) after the Armistice.

According to the original cemetery register and Grave Registration forms, no concentrated graves were brought in to Railway Chateau Cemetery, although it is conceivable that graves have been regrouped?

The Unknowns

There are 6 unknown burials in Railway Chateau cemetery; 5 are buried in a collective grave, row B grave 6, with 1 in collective grave 8, row B. As all the unknown collective graves are amongst the November 1914, its probable that the unknown are from this period. Indeed, grave number 6 row B (containing 5 of the unknown) also contains 4 known burials of 1914. None of the unknown headstones have even any partial identification!

The Burials

57437 Gunner Sidney Herbert Toll

Sidney died of wounds on the 11th November, 1914 and is buried in row B, grave 5. He was the son of Charles and Eliza Toll of East Ham, London and served with the 47th (Siege) Battery, Royal Field Artillery (part of 44th Brigade, 2nd Division).

His brother’s name, Private Frederick William Toll, was added to the original register entry for Sidney, in pencil. He served with the 2nd Battalion Essex Regiment and died on the 8th August, 1914, shortly after the battalion was mobilised and whilst they billeted in Cromer, Norfolk. (Research on going)

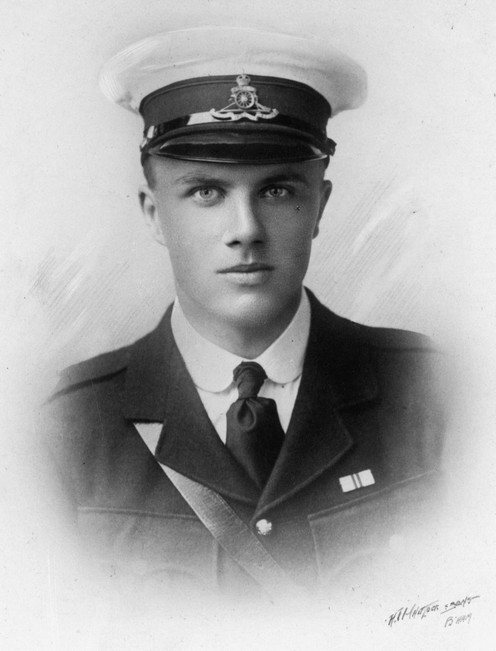

Lt. George Frederick Cottrell

George was killed in action on the 11th May, 1915, the first of 12 officers and men serving with the 108th Heavy Battery, RGA (attached to 28th Division). He was previously a colour sergeant in the Officer Training Corps (OTC), at King Edward’s School, Birmingham. He received his commission from the Royal Military Academy (RMA), Woolwich in July 1913, embarking for France in September 1914, where he served with the Indian Army and later transferred to the 108th Brigade in January 1915.

He is commemorated on the Great War Memorial at St. Augustine’s Church, Edgbaston.

His brother, 2/Lt. Harold Cottrell, 2/South Lancs. also fell (30th September, 1916, buried Pozieres B.C).

Lieutenant George Frederick Cottrell. (Image and casualty details courtesy King Edward’s School)

G/329 Private Albert Tomlin

Albert is one of twenty servicemen buried at Railway Chateau, who fell during the construction of the Ypres defences, started in September 1917, during the Third Battle of Ypres. The vast majority of their CWGC headstones are engraved with their pre-Labour Corps regiments, whilst the original cemetery register details both their original regimental details and their Labour Company service number.

Albert had previously served with the 2/Queens prior to being transferred: firstly the 29th Middlesex Labour battalion and then on formation of the Labour Corps, he was transferred again to the 17th Labour Company. Albert had previously served in India for twelve years including the North West Frontier and was still on the reserve when war broke out. He was 45 years of age.

The Isle of Man in World War One (Part One)

Terry Jackson

The Isle of Man is an independent self-governing Crown Dependency and is situated in the Irish Sea between Northern Ireland and Barrow in Furness.

In the mid-19th Century, volunteer army units were created, the perceived threat still being France. By the Childers Reforms in the 1880s, the sole remaining Manx unit was designated as 7th Volunteer Battalion, The King’s, (Liverpool Regiment). As the Territorial Force formed in 1908 by legislation did not include the Island, 7th Battalion was the last volunteer unit in the British Army. (A detachment of nine men accompanied the 6th King’s to South Africa during the Second Boer War).

On 4 August 1914, the battalion was attached to the West Lancashire Division and was only one company strong. It was used for guard duties. A second company was formed three weeks later and a third just before Christmas. A service company was formed from these in March 1915 and posted to 16th (Reserve Battalion) The Kings. Liverpool Regiment. Some were retained in a new company that guarded the POW camp at Douglas.

In October 1915, the service company transferred to the 3rd Reserve Bn. Cheshires at Birkenhead and became 1st Manx (Service) Company. In January 1916, it joined the regular army’s 2nd Bn. Cheshire Regiment in Salonika as ‘A’ Company for the reminder of the war. At the Armistice of Mudros on 30 October 1918, it was with 84th brigade 24th Division north of Lake Doiran. A second service company was formed on 27 November 1916 at Bidston Camp, Birkenhead, which was later broken up to supply drafts for France.

The effect of the war on the local population was quite dramatic. In peacetime, the main trade was from the tourist trade. At the height of the season, the population could swell to 50,000 and there were over 2000 properties used as boarding houses with several hotels and the associated leisure facilities, public houses, theatres etc. There was also a camp in Douglas where young men could holiday under canvass

Tourism coincided with the advent of reliable steam ships from Liverpool to Douglas and the traditional Wakes Week holidays taken by the employees of factories especially in the mainland industrial towns. The visitors had money to spend when urban industry was closed, which also allowed renewal and renovation of machinery etc.

By 1913, more than 660,000 people were visiting each year (including day trippers), mainly on ferries from Liverpool. In 1907, Motor Cycle racing had come to the island and it was to develop into the TT (Time-Trial/Tourist Trophy) races. However, on the outbreak of WWI, the tourist industry was wiped out virtually overnight, as men returned home, which affected the livelihood of many island families.

On the 8th August 1914, the Aliens Restriction Act was passed. The Act was aimed at identifying enemy spies, but all enemy aliens who had worked in Britain, no matter how long they had been resident, had to register as an enemy alien. (British born wives also had to register). Failure to comply meant a £100 fine or six months in jail. On the mainland, hastily arranged accommodation included disused factories and ships. Movement was restricted to a 5 mile radius. The British Government realised the Island would be a secure site for controlling enemy aliens and approached the Manx government for assistance.

In September 1914, two hundred male internees were shipped to the Island. They were placed in Cunningham’s Camp in Douglas. This had provided tented holiday accommodation for up to 1500 single men who had by this time returned to the mainland on the outbreak of hostilities in order to sign up for service. Soon after the outbreak of the First World War, the camp was requisitioned for internment purposes. Renamed Douglas Alien Detention Camp, the all-male internees were a mixed group and ranged from the extremely poor to the very well educated and wealthy. The camp was later split into three sections. There was a privilege camp for those who could afford to pay for extra facilities (and also employ an internee servant), a Jewish camp, where kosher food and facilities for celebrating Jewish festivals were provided and an ordinary camp for the rest of the civilian aliens. The camp commandant was Colonel Henry William Madoc (1870-1937), the Island's Chief Constable.

By October 1914, there were 2600 men in the camp, with a period when it increased temporarily to 3300 to relieve overcrowding in London camps. This created a similar problem in the camp and along with boredom and complaints about poor food, led to a riot in November 1914 during which five internees were shot and killed by the guards. An inquest found the actions of the guards justifiable due to the riot. However, it was realised that a bigger additional camp was needed. This brought about the construction of the Knockaloe Alien Detention Centre near the west coast of the island, one and a half miles south of Peel. The site had been used in the past for training the volunteers. It was much larger than the Douglas camp. It was arranged into four sub-camps of wooden huts and was within a barbed wire fence. By 1918, it housed over 20,000 men. Men were allowed to wear their own clothes and have personal items such as books. The men started workshops, art classes, theatrical groups and a school. After the armistice, the internees were gradually released from both camps so that by the summer of 1919 Cunningham’s had reverted to its original use. Knockaloe was subsequently dismantled.

The Naval War was obviously a key factor in the Island’s wartime experience and this will form part of a separate article, including the experiences of the Manxmen and Manxwomen who served in the conflict.

The reason for my interest in the Island is that I do have Manx blood in me. In 1944 my Stockport father Ronald was training on the Island in the RAF ground crew. Whilst there, he met a local young lady, Florence Gertrude Taylor. They married in 1944 and I was born 3 years later in Stockport. My father, like me was an only child. Florence had 7 siblings. Two of the men stayed on the Island. The other two men and the women all settled on the mainland. One brother, Bill, emigrated to Australia & I twice stayed with him and his family on my trips there. The last time, Ann accompanied me down under.