The Dragon’s Voice

In this edition, we have articles by Steve on Westouter churchyard and some of the casualties there, by Terry on dazzle camouflage for ships, and a book review of Professor Alex Watson’s excellent book on the German and Austrian aspects of WWI.

For obvious reasons, we have no face to face branch meetings for the foreseeable future, but there is a Zoom meeting (of the Stockport branch) coming up on 12th March, which anyone can join in, and is on their website – www.landcwfa.org.uk.

(Westoutre) Westouter Churchyard & Extension

Steve and Nancy Binks

We visited Westouter on 26th July, 2012, a very hot day, which had delayed our start until late afternoon, so avoiding the midday sun. This was my second visit, as in 2006 I came here with a battlefield tour group, in the footsteps of Gunner Tyrie, Tank Corps, who was killed during Third Battle of Ypres in October 1917.

Westoutre & Wartime Location

The town is four miles south east of Poperinge and 7.2 miles south west of Ypres, close to the Belgian/French border, a mere 1,700 yards to the west. It lies on the lower slope of the great ridge that encloses Ypres from the south west and terminates to the north east as the Passchendaele Ridge. The burial ground lay 9,000 yards east of the frontline trenches of November 1914, increasing to almost 15,000 yards after the Battle of Messines of June 1917. Until 1918, the town was concealed from direct observation by Mont Kemmel, Mont Rouge and the Scherpenberg. But despite this concealment and distance, trench maps don’t show any rail network or camps until after November 1917. After the German Lys Offensive, the front lines were just 2,600 yards distance to the east. Westoutre was positioned within the sector defences, with Westoutre coming within the French sector until August 1918.

Burial Ground Origins & Chronology

The 2nd Cavalry Field Ambulance came through Westoutre during the Cavalry Corps advance towards the Messines Ridge during October 1914. However, it was the 3rd Divisional Train that made the first burial in November 1914, as it was stationed close by. Driver James McIntyre, (26th November) was buried close to the civilian burials in what is now Plot 1 row F grave 4:

1914 1

1915 23

1916 10

1917 56 (Mostly September)

1918 7

Also, there are one unknown Canadian and three German burials.

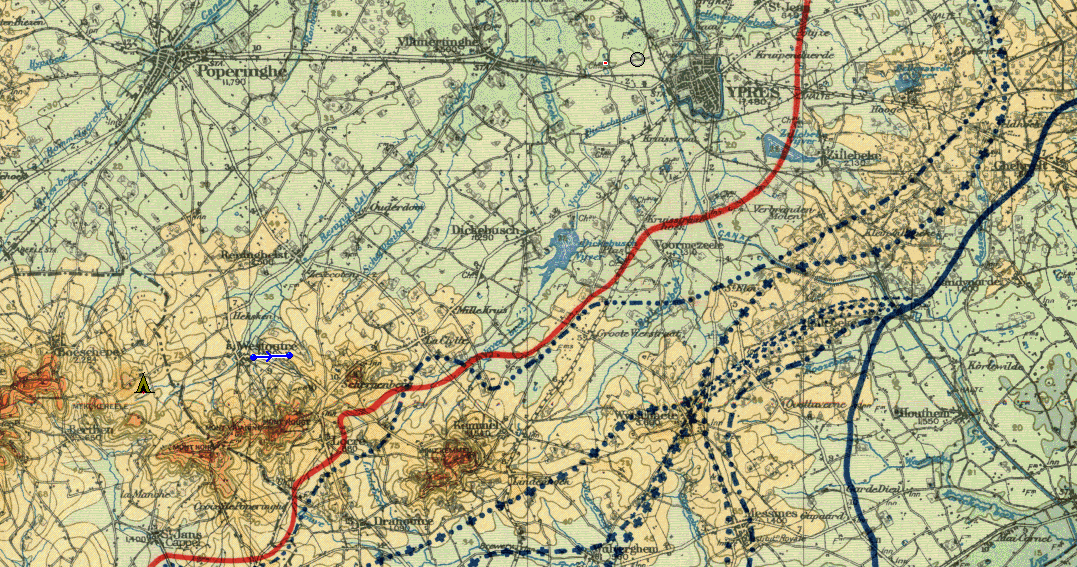

Location of Westoutre in relation to the various front lines of Third Ypres. The camp icon to the west of Westoutre was the location of the air raid on the 1st October 1917 (see later story)

From November 1914, the sector was taken over by the French until February 1915, after which the BEF began to extended their left flank. Westoutre was then used extensively as divisional headquarters, together with their ancillary unit headquarters: artillery, engineer, veterinary etc. Medical units occasionally used the hospice and its grounds as a dressing station but the town was particularly associated with its baths (in the brewery) and as the location for a divisional rest station (DRS), at the girl’s school, and its surrounding fields. After the burial of Lieutenant Colonel Stuart (GSO1, 50th Division), in June 1916, there were no further burials in the churchyard until February 1917.

From a review of many war diaries (using “Westoutre” as the search term), the medical units came and went on a regular basis. It was more regarded as a headquarters for the ADMS (Assistant Director of Medical Services) of a division, with perhaps just one section of a field ambulance. When the 112th (16th Division) Field Ambulance (FA) took over the hospice in September 1916, the war diary records that nuns and inmates still occupied the building! This unit carried out many improvements and by March 1917, the 112th FA diary reported that it could accommodate 138 cases: “27 on the ground floor, 71 in the attics and 40 in the school”. I believe the school later became the Divisional Rest Station (DRS), taking in lightly wounded and the sick.

The vast majority of the burials - almost 50% - were made by X Corps (23rd, 39th and 41st Divisions) during the renewal of the Third Battle of Ypres September/October 1917. The 23rd Division ADMS war diary for the period records that the DRS was in a poor state (as was the sanitary conditions) having not been used for some time and consisted of “just a few bell tents”.

On the outbreak of the Battle of Menin Road (20th September), X Corps FA’s struggled to clear casualties through lack of transport, resulting in FA’s clearing other division’s casualties. The 23rd Division responded by moving two operating tents to Westoutre together with all remaining casualties at their ADS’s. (On the 30th September, the 69th FA handed over their MDS at Dickebusch and marched to Westoutre where they took over the Hospice.) During this period, burials in the churchyard stopped and a new British cemetery opened, a short distance from the hospice.

In April 1918, the sector was again taken over by the French and just a handful of burials followed the final allied advance, from August 1918.

Image taken from the eastern corner, looking across plot 2 on the far side and plot one, to the right hand side of the Belgian civilian graves. I usually include a cemetery plan with burial sequence, however given the “confused” layout, it would have served little benefit to the readers’ understanding.

Burial Ground Layout

The earliest burials, up to October 1915, were made in narrow rows to the left hand side of the civilian graves, (on the right hand side of the central path). These 16 graves now form plot 1, rows A – F, after which burials were made in an extension, to the left hand side of what is now plot 1. The extension* was started by the 4th Canadian Field Ambulance that established its “A” section in: “two buildings; one a hospice for medical cases and the other a girls’ school for surgical cases.” They arrived in Westoutre on the 20th September 1915, relieving the ADMS, 28th Division, and remained until 3rd April, 1916.

The cemetery plan (from the first register, dated circa 1928) details “Belgian Civil Graves”, in front of what is now plot 2, therefore it can be assumed the extension was made within the existing boundaries of the churchyard. The length of rows in the extension was limited by the church wall boundary to the north and east and the path to the south.

After the opening of a further burial ground in Westoutre, only a handful of further burials were made.

* The earliest burial ground register contains the names of only the original 16 burials of plot 1, with a separate register for the extension, which was later amalgamated.

The Burials

There are many non-infantry graves, including artillery, tank corps, ASC, and RAMC. No single infantry unit has more than a handful of burials, but there is a clear spike of X Corps burials in September 1917, specifically around the Battle of Menin Road (20th September). These include mostly 41st Division units: 20/DLI, 21/KRRC and 26/RF, likely to have been cleared through 23rd Divisions’ evacuation lines.

There are seven burials of other ranks from the 24th Battalion, CEF, made between 2nd October and 29th December 1915. This represents the largest number of burials from one unit. Their first casualty, Private 65799 C W Price, died of a perforated lung, sustained from wounds during the battalions first tour of the trenches, near Petit Bois. He was also the first Canadian casualty buried at Westoutre Churchyard.

The layout and sequencing of the burials gives little indication of any detailed organisation when compared to other field ambulance burial grounds. For example, the 45 burials of 1917 are buried in all six rows of plot 2 (the extension): the first 1917 burial in row D, second in row B, eight in row A, seventeen in row C, etc. There is no evidence of units attempting to create “a battalion burial ground”, thus keeping their casualties grouped. Some of the later burials extended several of the rows to both the northern and southern side, indicating that space was a premium and starting an additional row wasn’t possible or practical. Spaces between graves had by the armistice been in-filled with later burials. There were no concentration burials brought in from the battlefield or other burial grounds.

The Men

A review of our “Cemetery Visit Form”, completed at the time of our visit in July 2012, records that I made a note stating: “3 x Robinson’s buried side by side”. On review of the on-line cemetery register, its noted that two of these men are brothers, who died on the same day, in different units and buried in the same grave: plot 2 row A, grave 5:

MS/1566 Private Charles Frederick Robinson, 594th MT Coy (ASC)

81330 Gunner James Alfred Robinson, 12th Bty 35th Brigade, RFA

Both men died on the 16th September, 1917, probably at the 69th FA Main Dressing Station (MDS).

They were sons of Mrs. Robinson, Medway Road, Bow, London. The latest on-line CWGC archives has a file against “Westoutre” under the family name.

On the 1st January, 1918, Mrs. Robinson wrote to the Graves Registration requesting photographs of three sons! It transpires that her third son was killed on the 24th August 1916 (serving with 7/DCLI) and buried at the time in the North West corner of Bernafay Wood (Somme). In October 1920, graves from this spot were exhumed and reburied in Bernafay Wood Cemetery, on the opposite side of the road. Private William Robinson’s grave could not be found and his headstone in Bernafay Wood Cemetery was marked by Special Memorial.

In December 1937, the family was informed that further excavations had taken place in the North West Corner of Bernafay Wood and that Private William Robinson’s remains had been found and subsequently buried in Plot V11, Row B, in London Cemetery Extension, High Wood.

Further correspondence from the mother includes the words; “I have been given to understand that they [the two brothers buried at Westoutre] were killed together and are buried together”. On first view, it seems as though the brothers served in different units: RFA and ASC, but given their mother’s letter, its likely 594th Motor Transport Company was attached to the 12th Battery!

During our visit, I photographed the grave of 18027 Private Arthur William Hall, 10/ West Yorkshire Regiment, 29th July, 1915, age 33, buried in plot 1 row E, grave 2. Earlier visitors had placed a framed picture of him on his grave.

Arthur was born at Thirsk, Yorkshire in the third quarter of 1882. He was a farm labourer who gained experience with horses. He married Eliza Metcalfe at Thirsk in 1902 and later lived at Sowerby where he continued to be employed as a farm labourer. The couple had seven children before Arthur enlisted in to the 10th battalion West Yorkshire Regiment (17th Northern Division) at York on the 30th January, 1915.

The division arrived in Belgium during July 1915 and units began a period of trench training; the 10/West Yorks with the 1/6th Sherwood Foresters in J trench, near Petit Bois.

Arthur (number 5 platoon, B coy) was the battalion’s first casualty. Wounded by enemy shelling, he was evacuated to 85th (3rd London) FA at Westoutre, where his leg was amputated. Sadly, he later died of blood poisoning.

His wife gave birth to a further child whilst her husband was serving overseas; a child he never saw. (Information and inset courtesy of steveward.co.uk and Wetherby War Memorial site).

Private William Tyrie*, Tank Corps

In plot 2, row F, graves 14, 15, and 16, are three casualties of A battalion, 4th Tank Brigade, whose date of death is recorded as 1st October, 1917. These casualties have been a bit of a mystery to me (see opening paragraph) and further research through the Great War Forum has failed to pinpoint the cause and circumstances of their deaths. Unusual for tank corps casualties, there is no mention of their death in the war diaries, which are usually very detailed about tank crews and their actions.

Using the National Newspaper Archive, I searched the name “Tyrie”, and luckily got a hit. The Forfar Dispatch reports:

“A communication from an officer received by his father gives some account of William’s death. It appears that along with three others of the crew he was guarding an exposed bit of ground when he and another two were killed and a fourth wounded”.

Unfortunately, it fails to mention their location. If the men were on the front line (around Clapham Corner, east of Hooge) it is unlikely their bodies would have been brought all the way back to Westoutre for burial!

It is known there was an air raid on the night of the 1st October (known to have killed at least eleven men belonging to 14/Hampshires). One of these men is buried adjacent to the tank crew in Westoutre. Their being no further space available, the other ten were buried in Westoutre British Cemetery. Could this have been the incident? I’ll keep researching.

*A brother, Seaman John Tyrie, Royal Naval Division was killed in action at Gallipoli

The Inventor of Dazzle Camouflage

Terry Jackson

Norman Wilkinson CBE RI (24 November 1878 – 30 May 1971) was a British artist who usually worked in oils, water colours and drypoint. He was primarily a marine painter, but also an illustrator, poster artist, and wartime camoufleur. Wilkinson invented dazzle painting to protect merchant shipping during WW1. He was born in Cambridge, England and attended Berkhamsted School, Hertfordshire and St. Paul's Cathedral Choir School in London. His early artistic training occurred in the vicinity of Portsmouth and Cornwall, and at Southsea School of Art, where he was later a teacher. He also studied with seascape painter Louis Grier. While aged 21, he studied academic figure painting in Paris.

Wilkinson's career in illustration began in 1898, when his work was first accepted by The Illustrated London News, for which he then continued to work for many years, as well as for the Illustrated Mail. Throughout his life, he was a prolific poster artist, designing for the London and North Western Railway, the Southern Railway and the London Midland and Scottish Railway. It was mostly owing to his fascination with the sea that he travelled extensively to such locations as Spain, Germany, Italy, Malta, Greece, Aden, the Bahamas, the United States, Canada and Brazil. He also competed in the art competitions at the 1928 and 1948 Summer Olympics.

During the First World War, while serving in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, he was assigned to submarine patrols in the Dardanelles, Gallipoli and Gibraltar, and, beginning in 1917, to a minesweeping operation at HMNB Devonport.

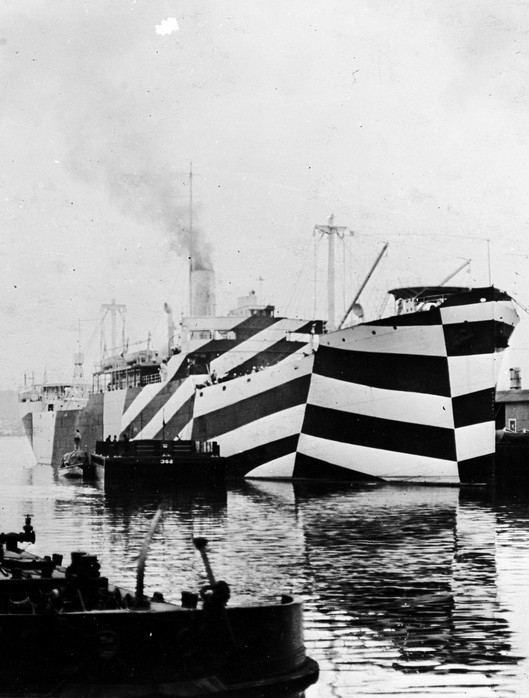

In April 1917, German U-boats achieved unprecedented success in torpedo attacks on British ships, sinking nearly eight per day. Wilkinson arrived at what he thought would be a way to respond to the submarine threat. He decided that it was all but impossible to hide a ship on the ocean (if nothing else, the smoke from its smokestacks would give it away) Thus he thought how could it make it difficult to aim at a ship through a periscope? He decided that a ship should be painted "not for low visibility, but in such a way as to break up her form and thus confuse a submarine officer as to the course on which she was heading”.

After initial testing, Wilkinson's plan was adopted by the British Admiralty, and he was placed in charge of a naval camouflage unit, housed in basement studios at the Royal Academy of Arts. There, he and about two dozen associate artists and art students (camoufleurs, model makers, and construction plan preparators) devised dazzle camouflage schemes, applied them to miniature models, tested the models (using experienced sea observers), and prepared construction diagrams. These were used by other artists at the docks (one of whom was Vorticist artist Edward Wadsworth) in painting the actual ships. Wilkinson was assigned to Washington, D.C. for a month in early 1918, where he served as a consultant to the U.S. Navy, in connection with its establishment of a comparable unit (headed by Harold Van Buskirk, Everett Warner, and Loyd A. Jones).

After the war, there was some contention from other artists about who had originated dazzle painting. However, at the end of a legal procedure, Wilkinson was formally declared the inventor of dazzle camouflage, and awarded monetary compensation.

Second World War camouflage

During the Second World War, Wilkinson was again assigned to camouflage, not in dazzle-painting ships which had fallen out of favour, but with the British Air Ministry where his primary responsibility was the concealment of airfields. He also travelled extensively to sketch and record the work of the Royal Navy, the Merchant Navy and Coastal Command throughout the war. An exhibition of 52 of the resulting paintings, The War at Sea, was shown at the National Gallery in September 1944. It included nine paintings of the D-Day landings, which Wilkinson had witnessed from HMS Jervis, plus naval actions such as the sinking of the Bismarck. The exhibition toured Australia and New Zealand in 1945 and 1946. The War Artists' Advisory Committee bought one painting from Wilkinson; he donated the other 51 paintings to the Committee.

Wilkinson was elected to the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours (RI) in 1906, and became its President in 1936, an office he held until 1963. He was elected Honourable Marine Painter to the Royal Yacht Squadron in 1919. He was a member of the Royal Society of British Artists, the Royal Institute of Oil Painters, the Royal Society of Marine Artists, and the Royal Scottish Society of Painters in Watercolour. He was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in the 1918 New Year Honours, and a Commander of the Order (CBE) in the 1948 Birthday Honours.

Book Review

Ring of Steel

Alexander Watson

Penguin Books, London 2014

This book deals with the German and Austro-Hungarian side of WWI events. It is in English, thankfully, as most books dealing with this aspect of WWI are in German.

Alex Watson is the rather youthful Professor of History at Goldsmiths College in London. He is an excellent speaker and his writing follows that vein. His style is very readable and rather reminiscent of a journalist’s prose. This makes the book very easy to digest. It has nominally almost 800 pages, but in fact some 220 pages are references, so the actual text is 560 pages. However, it is, as I have said, easy reading. He uses maps, tables and photos to bring the text to life, as it were, which is not always the case with historical books.

The “ring of steel” of the title refers to the perceived encirclement of Germany, and of Austro-Hungary, by Russia to the East, France and Britain to the West and, eventually Italy to the South. The inclusion of analysis of the Austro-Hungarian position gives a more complete picture of the wartime events. Indeed, Austro-Hungary played a more important role than it is often given credit for. This ranges from being in many ways the cause of the war to the major battles in the East, notably the sieges at Przemsyl and the winter war in the Carpathians in 1914/15. The Russian threat to Germany and to the Austro-Hungarian Empire was in many ways diminished by these events, but at the cost of dragging Germany into more of the war in the East.

The entry of Britain is described as radicalising the war, by the use of economic means and turning it from being a purely military affair into a grinding attritional contest that assailed whole communities and turned civilians into targets. The British naval blockade is often overlooked by British historians, but not here. The effects of the blockade were felt not only by the German civilians but more so by the beleaguered Austrians who had also lost much of the agricultural area of Galicia to the Russians. Starvation of Belgian and French civilians was alleviated by a US relief programme devised by Herbert Hoover, who was later US president.

The Germans compared the British naval blockade to the British imperial regime causing the potato famine in Ireland, with about one million deaths, which the author points out was closer in time to WWI than WWI is to us today. The author even mentions the sinking on 10th October 1918 of the RMS Leinster, off Dublin, an event key to Woodrow Wilson’s hardened response to German approaches for an armistice (even if the more accurate death toll of 565 was not known when the book was published). This is an event often ignored by British historians.

Attacks on the civilian population are dealt with. Often books on WWI agonise over the attacks on Belgian and French civilians in August and September 1914, but here the author also describes the massacre of civilians in East Prussia by the invading Russians in 1914. However, by far the worst of these massacres was by the Austro-Hungarian army of its own citizens – the Ruthenes in Galicia of whom 25,000 to 30,000 were massacred in 1914-15, for largely imaginary acts of treason. The Jewish populations suffered also, though often at the hands of their fellow citizens. Pogroms against the Jews continued in the “new” countries such as Poland, and also Russia, well into the 1930s.

The author shows up various WWI myths, and uses tongue in cheek terminology for some of the odder aspects of the war. So, the American plan to string mines across the North Sea from Scotland to Norway to stop German submarines is described as megalomanic, quite justifiably. Ludendorff, the de facto German strategist after late 1916, is described by his nominal title of First Quartermaster General. So, the quartermaster is in charge of the army!

The mess of the British preparations for the Somme, courtesy of Haig, is described, as is the tactical clumsiness of the British in the spring of 1918, when they were rescued by the toughness of the rank and file.

The issue of the losses of professional officers on the German army in the early stages of the war is analysed. It is an issue often glossed over by historians. The class system of the officer corps acted as a restraint on promoting NCOs to the officer ranks. All this combined to reduce the fighting efficacy of the German army (or, in reality, armies). The situation for the Hapsburg army was worse. Its NCO corps had been hit even harder in the early phase of the war. The Hapsburg army lost 2.7 million soldiers, NCOs and officers in the first year of the war. Age limits for service were widened and training for new recruits was shortened. Both armies suffered from young officers who were dropped into situations that they could not cope with.

The situation on the home fronts is analysed. The public mood, of course, changed over the four years of the war, from euphoria to suffering and shortage. A letter from a Hamburg lady is quoted as having in 1916 witnessed a scramble to buy meat, in which two women were killed and sixteen hospitalised. Town dwellers took to the countryside to buy or steal provisions from farms. In peacetime, Germany had depended on food imports. Now, many farm workers were in the army, or dead. Horses had been requisitioned for the army. In Austria, Vienna especially suffered. The territories of Galicia and the Bukovina were devastated after the Russian invasions. They were very important for food supply of the empire. Animal manures for use as fertiliser were reduced as there were fewer animals. Ammonium nitrate artificial fertiliser was diverted to make munitions. A fallout over supplies between Austria and Hungary made matters worse for Austria, especially Vienna.

The treaty of Brest Litovsk, between the central powers and Russia in 1917 is critically analysed, without, as the author terms it, “the breathless horror” with which the terms are often recited. In fact, it left Russia with rather more land than it has today. The bulk of the land lost by Russia was the Baltic republics, Poland and the Ukraine. In fact, the Ukraine ended up back under Bolshevik Russian control after WWI, with brutal collectivisation of farms under Stalin and 3.3 million deaths from a man-made famine.

The disaffection of the peoples of Austro-Hungary and the demise of the Empire under Kaiser Karl are analysed. The Czechs and Poles gradually detached mentally from the Empire, with the ultimately successful aim of independence.

The effects of Woodrow Wilson’s apparently attractive “fourteen points” are examined. In effect, self- determination may have seemed a wonderful aim in the abstract, but Central and Eastern Europe was a mosaic of ethnic groups, living cheek by jowl. One person’s self-determination is another person’s being shoved into a new state where he is no better off than in the one he has just left. In many ways, it was a catalyst for much of the post-WWI chaos in the “bloodlands” of Central and Eastern Europe.

Overall, this book is a tour de force. It casts light into areas that have often been ignored by English-speaking historians, and gently debunks myths.