The Dragon’s Voice

Hello. In this edition, we have an update from Steve and Nancy, in particular on their experiences at Vimy, an article on a French heroine of two World Wars, a brief account of being on a WFA stall at a genealogy exhibition, and a local book review. As ever, many thanks to Jim Morris for allowing us to use his WWI day by day material on the Facebook page.

Trevor

The Programme for 2016

November 5th - Mountaineers in the Great War - Anne Pedley

December 3rd - Branch Social

The Programme for 2017

Jan 7th : Beer and Blather at the Albion

Feb 4th : Georgina Holme : Some Great War Commemorations in Anglesey

Mar 4th : John Sneddon : Bombay Sappers and Miners at Neuve Chapelle 1914

Apr 9th : Dr Graham Kemp : How the 10th Cruiser Squadron Won the War

May 6th : Jon Bell : Comparing Medical Services in the Great War with now

Jun 3rd : Stuart Hadaway : RWF and the Battles of Gaza and the Thomas Brothers

July 1st : Colin Walker : Scouts in the Great War

Aug 5th TBC

Sept 2nd : Taff Gillingham : Daddy what did you do in the Khaki Chums and Development of Uniforms and Equipment.

Oct 7th : John Stanyard : Under Two Flags, the Salvation Army in WW1

Nov 4th : TBC

Dec 2nd : Branch Social

Last month’s speaker

Marietta Crichton-Stuart came to see us again, this time talking about her grandfather, Lt Col Lord Ninian Crichton-Stuart. He was the CO of the 6th (Glamorgan) btn Welsh Regiment, which was TA. He was elected in 1910 as Unionist MP for Cardiff, having previously served in the Scots Guards. He was one of 22 MPs to be killed during the war. He was the second son of the Marquess of Bute, the family that owned Cardiff Castle, and it was after him that Ninian Park was named. He had stood guarantor for Cardiff City Football Club for the sum of £90.

Marietta has uncovered correspondence from her grandfather, including his last letter written on 1st October 1915. She has researched his life and followed where he fought and died, in the second phase of the battle of Loos. He was killed by a sniper as he stood on the firestep directing machine gun fire. His body was initially taken back to the church at Sailly Labourse which still exists today and he is now interred in Bethune town cemetery. After Loos, the 6th btn became a pioneer battalion. Of the 845 men who set out in 1914, only 30 were still in service at the end of the war.

All in all, it is a most interesting piece of family history!

Vimy Canadian Memorial

Steve and Nancy Binks

The Canadian National Memorial at Vimy Ridge was erected by the Canadians in honour of their countrymen who had participated in the Great War, particularly their 66,000 war dead. It was not intended to be a Memorial to their Missing. What follows is a short account of our visit as part of our “SomeKindHand” Pilgrimage and some of the things we learnt about the memorial during that visit. The views and thoughts expressed are those of Nancy and myself.

A Brief History

At the end of the war, an IWGC committee awarded Canada eight battle sites - three in France and five in Belgium - on which to construct memorials. Meanwhile the task of dealing with the “unknown” loomed large. The original idea was to commemorate them on 80 memorials, as close to where the servicemen fell as possible. For the British this proved an impossible task, however the dominions made progress.

In 1920, the newly established Canadian Battlefields Memorial Commission organized a competition for a Canadian memorial to be erected on each of the eight sites. In October 1921, the commission announced the winner: Walter Allward, whose design included twenty symbolic figures associated with war, (loosely based on the crucifixion). These figures formed an integral part of a massive stone platform surmounted by two soaring pylons representing Canada and France.

In the summer of 1922, the Canadian Battlefields Memorial Commission selected Vimy Ridge as the only site for Allward's winning memorial. The other battle sites, with the exception of that at St. Julien, which received the competition's second-place design, made do with less distinguished monuments and were clearly unsuited to the vastness of Allward’s design in terms of scale and cost. Vimy Ridge's impressive location and vantage point, as much as the battle's military significance, contributed to its selection, although Arthur Currie, the Canadian’s last Corps commander preferred Bourlon Wood.

Work on the Vimy Memorial started in 1925, by which time the IWGC had decided how to deal with the “Unknown”. France and Belgium had gifted sites on which the names would be engraved. However, as the years progressed the French became resistant to continual demands from the British for more and more land on which to build their memorials. As a result plans were scaled back and Memorials to the Unknown were reduced in number, some redesigned to stand within British cemeteries. Blomfield’s Menin Gate Memorial, for example, was redesigned to carry 60,000 names.

The Canadians had therefore already committed to include the names of their 18,650 unknown; only the negotiation skills of Fabian Ware convinced the Canadians to commemorate their missing in the Ypres Salient on the redesigned Menin Gate and therefore Vimy commemorates the Canadians with no known grave in France.

Visit Preparation

Usually, our visits to the many varied burial grounds require little more work than: suitable clothing for the day’s weather, a packed lunch, visit sheets, camera and a good sat nav. Occasionally, the odd “Route Barre”, cemetery maintenance programme, or a lost grave in a communal cemetery can slow down our Pilgrimage. Once in a while - particularly memorials to the missing - a little more groundwork before we start reading the names is required. Most importantly, a key issue is whether the names are legible, readable and accessible. This involves a pre-visit “survey” to the memorial and a check on the website of the CWGC to ensure there is no work scheduled that will impact on our visit. Typical was the recent reading of the Vimy Memorial.

I realised that unlike most of the CWGC memorial sites, Vimy does not have an on-site holder for the memorial registers, so part of the pre-visit survey was to inquire if registers were available; as, whilst I read the names, Nancy reads the register. A quick inquiry at the Canadian visitors centre at Vimy brought about blank faces from the staff as to why we needed registers when a full list of names was available on their computer. A fuller explanation of what we were about to undertake wasn’t understood either. Undeterred, we went to the CWGC headquarters at Beaurains to find out why there were no registers at Vimy. After several phone calls and emails, (between the CWGC and Canadian Veteran Affaires), we understood that the head gardener, whose responsibility the registers fall under, had been unsuccessful in previous attempts to “deliver” them and therefore no longer bothered. Nelly at the CWGC was as good as her word and emailed us to confirm that a set of registers was now safely in the custody at Vimy.

The Pilgrimage Starts!

So, on a damp Monday we set off to read the names on the Vimy Memorial, reckoning on two or possibly three days – dependant on the weather – to complete. Needless to say when we got to the visitors centre they knew nothing of the registers that had been “delivered”! However, after a few calls we were glad to hear that someone would meet us up by the memorial gates with the said registers.

Although it wasn’t particularly straightforward, we drove from the temporary car park up to the memorial car park, where I got Nancy organised into her wheelchair. As I did, I could see the guide standing by an official Canadian Affaires vehicle, but as quick as I tried to rush Nancy, the guide drove off in the direction of the administration buildings. A tad cheesed off we vowed just to get on with the reading and forget the registers.

I had forgotten how steep and close the steps are up on to the memorial. But anyhow undeterred, I managed to get Nancy, wheelchair and myself on to the memorial; going down (the other side) is usually a little easier. However, the start of the named panels was cordoned off by a maintenance team and wasn’t accessible. Toys came out of the pram and off we set for somewhere else, passing the guide with the registers on our way!

Realising that almost all our intended Pas de Calais burial grounds and memorials had been covered and that Vimy was “calling”, we returned a week later having been informed that the work was scheduled by Canadian Veteran Affaires and not the CWGC. Thankfully the named panels remained accessible for both days. We just could not be bothered with the to-and-fro journeys to the visitors centre in attempts to gain possession of the registers.

How the names are organised

For those unfamiliar with the Vimy Memorial name panels, they wrap around three sides (at ground level) of what I think looks like a large oblong wedding cake stand. These panels cover letters L (cont.) to Z. To access the panels lettered A to L (start), you have to climb the stairs on to the memorial and then descend another flight to the viewing panel, and where the remaining names stretch - interrupted only by the staircase – the entire length of the memorial.

Names are organised alphabetically, then by rank; unlike the usual regimental order of precedence. Duplicated names are indicated with service numbers. There are no lieutenant colonels on the Vimy memorial, the highest rank being major. There is also no distinction between lieutenant and second lieutenant; sergeant is spelt the English way. Under regimental precedence, there would be separate listings for artillery, engineers and cavalry, but not at Vimy. They have had to make a decision about rank precedence across the varying arms of the military. There are six Victoria Cross recipients on the memorial and these are identified with VC engraved after the name. It is the only memorial that I have yet read that has “Bars” to bravery medals engraved.

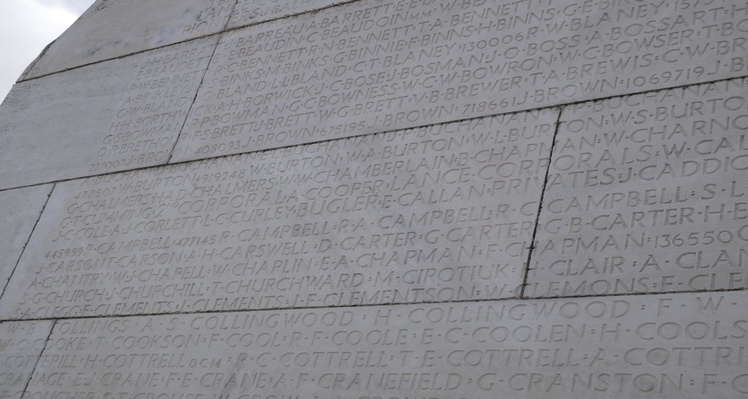

The panels were re-engraved as part of a complete refurbishment of the memorial, 2005 – 2007 and are crisp and clear. They are mostly at eye level so no neck straining, or binoculars needed! Reading was from left to right and top to bottom. The memorial’s stone supports act as a natural break to ensure that you can stand on one spot and read an entire panel. However on the front of the memorial, i.e. on the viewing platform the names are continuous, only broken because of the central staircase, even extending across the walls of the side staircases. This requires the reader to walk left to right for some 40 metres and then return back again like some old typewriter to read the next row! This took some extra concentration, as Nancy kept count on the row number.

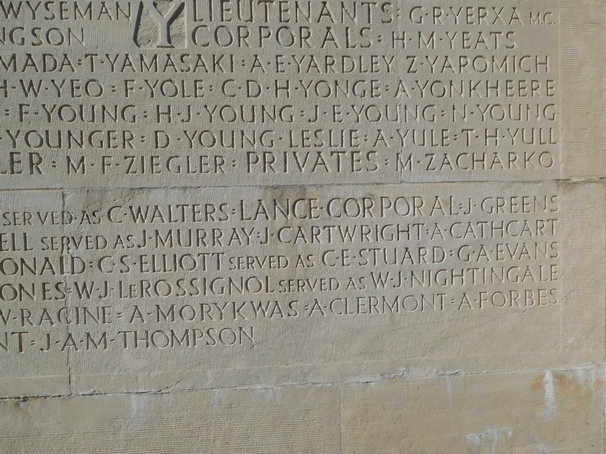

There are at least 11,265 names engraved on the Vimy Memorial, but only 11,161 commemorated. This is through the likely finding of graves in the post war years. However, no names have ever been removed as there are no gaps; names are engraved directly on to the memorial walls (or stone blocks), meaning that blocks cannot be re-engraved without impacting the blocks on either side, top and bottom. And so on, as names run across the gaps in the “grout”. (See Fig.1)

The Pilgrimage gets underway

The sun shone but the breeze was quite strong as we started the reading. As the journey up the stairs the previous week had nearly killed me, I decided to start with the panels on the front of the memorial; this corresponded with the letter O.

After a successful first day where the only problem was a strong breeze, we returned the following day to a much stronger wind AND we now faced the task of the names across the walls of the viewing platform, more open to the elements. By a simple calculation, if all went well on the second day, we should complete the reading!

Apart from losing the line a couple of times, especially where the names descend the staircase we completed the left hand side in time for lunch. Now, normally we eat lunch with “the Boys” in the cemeteries; the memorials are different and we felt it was inappropriate to lunch at Vimy so we had already decided to return to the car park for lunch; I didn’t count on having to climb those stairs again though! Getting the wheelchair and Nancy up the stairs is all about momentum. At Vimy the steps are high with a narrow width. With the high wind I struggled to get the necessary momentum and about five steps up really began to struggle to hold Nancy at the required 45o. Each step now became a single challenge. About three steps from the top my knee gave way and the wheelchair trapped my legs. Nancy was now in her chair on top of me at 90o! We were in real trouble. Thankfully one of the Polish lads working on the memorial heard me call for help and came running over to save the day. I learnt a valuable lesson about taking a wheelchair upstairs on my own. I dread to think about some of the isolated cemeteries with extraordinary steps that we have negotiated without a thought for Nancy’s safety! With real difficulty and support Nancy CAN climb stairs as long as there is a rail or a wall. As Nancy keeps saying - which I always ignore - “I’ll walk”. Needless to say I didn’t take Nancy back after lunch; unhappily she had to remain in the vehicle.

The memorial always seems to be perpetually busy with visitors. I noticed that school groups tended to swarm over the memorial in the morning; the afternoon therefore seems quieter. Surprisingly, (in my opinion on what I witnessed) few people who visit the memorial come to read the names. I rarely get interrupted although my reading of the names is quite audible. Reading names is a very lonely business. Occasionally I do become aware of people stood listening to my voice and this heightens my sense of duty and focus. That afternoon it was a middle aged couple from Bolton (now living in France). Quietly she whispered to me, “They can hear you, you know?”

Figure 1 (left). Part of the addenda panel which includes names originally omitted, mainly those who served under an alias. One such soldier was Private W.J. Le Rossignol, who served as W. J. Nightingale; the French name for Nightingale! Notice how the names run across the grout lines.

Figure 2 (right). Names on the left hand elevation showing the natural breaks in the names created by the stone supports. Note the three memorial crosses, precision placed in the corners. Clearly an attempt by Canadian Veteran Affaires to keep the memorial tidy. There was not one photograph or any personal mementoes placed, that comes to be expected on memorials to the missing. Note the striped grass. The majority of maintenance of the sight is carried out by Canadian Veteran Affaires; CWGC gardeners would not waste their efforts. One has the impression that the Canadians are attempting to emulate American Memorials. It is not surprising that memorial registers are not openly available on site.

Figure 3 (left). A section of the names on the viewing platform side (not sure if this is the back or front of the memorial) and the continuation down the staircase. I think this is a clear indication that the memorial was never originally intended to be a Memorial to the Missing!

Figure 4 (right). Centre of picture is the name of Bugler Edward Callan, the only Bugler commemorated on the memorial and the first serviceman to fall in the C.E.F with no known grave.

Emilienne Moreau-Evrard: French Heroine of Two World Wars

Caroline Adams

In June 1914, the Moreau family moved to Loos-en-Gohelle. Having previously worked as a miner, Monsieur Moreau was looking forward to an easier life as a shop keeper. Emilienne was 16 and planned to study to become a teacher. By the end of the year, however, Loos had been occupied by the German army and Monsieur Moreau had died.

The German occupation caused severe privation for the people of Loos. Early in 1915, Emilienne improvised a school for the local children in a cellar but when the Black Watch counter attacked the village in September 1915, she decided to take an even more active part in proceedings. She managed to pass to the British information on the positions of the German troops and later helped to set up an improvised field hospital in her own house and helped to bring in the wounded. She also carried grenades and accompanied several British soldiers when they went to deal with two German soldiers who were firing from a neighbouring house and later used a revolver against two more Germans who were outside her house.

The German occupation caused severe privation for the people of Loos. Early in 1915, Emilienne improvised a school for the local children in a cellar but when the Black Watch counter attacked the village in September 1915, she decided to take an even more active part in proceedings. She managed to pass to the British information on the positions of the German troops and later helped to set up an improvised field hospital in her own house and helped to bring in the wounded. She also carried grenades and accompanied several British soldiers when they went to deal with two German soldiers who were firing from a neighbouring house and later used a revolver against two more Germans who were outside her house.

In November 1915, Emilienne was presented with the Croix de Guerre avec palme. Her story was publicised widely throughout allied-held France. Her memoires were published in a newspaper in December 1915 and postcards were produced with her picture to inspire the troops. She also received from the British the Military Medal, the Royal Red Cross and the Order of St John of Jerusalem.

Emilienne did train and work as a teacher. In 1932, she married Just Evrard, secretary general of the Socialist Federation of Pas-de –Calais. Two years later she became secretary general of the women’s branch of that organisation and this took up her energy till the Second World War.

In 1940, her fame from 1915 came back to haunt her. The Germans had also heard the tales of the ‘Heroine of Loos’ and she was placed under house arrest for a short time. Thereafter, Emilienne and her husband became part of the Resistance. Throughout the rest of the war, they worked in different parts of France with various different networks and using different names.

After the war she was involved with the socialist party and trade unionism and was president of the Pas-de-Calais veterans’ federation. She died in 1971. Her full list of awards was:

Officier de la Legion d’Honneur

Compagnon de la Liberation

Croix de Guerre 1914-1918 avec palme

Croix de Guerre 1939-1945

Croix du Combattant 1914-1918

Croix du Combattant Volontaire de la Resistance

Military Medal (GB)

Royal Red Cross – first class – (GB)

Order of St John of Jerusalem (GB)

References: Alexandre Villedieu Facebook Page

http://www.ordredelaliberation.fr/frles-compagnons/321/emilienne-moreau-evrard

Who do you think you are?

I was helping with a WFA stand at a genealogy exhibition in Dublin and came across the following queries.

Two brothers who were orphaned and were sent to Canada before WWI. They joined the Canadian army at the outbreak of the war and served in WWI. Both survived. The Canadian service records still exist and are now on line, so we tracked the soldiers down very quickly. One even had dental records!

A family who thought they had found one WWI soldier in a civilian grave in Dublin but it turned out to be two brothers who both died shortly after having been brought back from France at the end of the war. We found the name of the hospital where one died, and found the names of the relatives to whom the soldiers’ gratuities were sent.

An RAMC orderly who from his medal index card was “in theatre” as early as 27th August 1914. We explained to the relatives the situation for the BEF at that time. He survived the war, finishing as a staff sergeant. He is believed to have been a quartermaster and after the war ran a successful chain of small shops.

A soldier from County Cork who joined the RHA in 1912, served throughout the war as a driver, was demobbed in January 1919, rejoined for the British North Russia Force in June 1919 and deserted back in Ireland in June 1920. There is a wonderful “jobsworth” letter on the file from an officer complaining that the soldier cannot rejoin the RGA in 1919, he has to rejoin the RHA and be posted to the RGA!

A Town at War – Denbigh and the Western Front

by Cliff Kearns

DolAwel publishing, £10

The Denbigh Historical Society have been running a WWI exhibition in the Denbigh museum over the last few weeks, which has generated a lot of local interest. Coinciding with that, a book of the letters and press reports of the Denbigh soldiers has been put together by local author Cliff Kearns. This gives eye witness accounts of their experiences which, frankly, are worth more than the ponderings of hordes of academic writers who were not there.

Local aspects of the formation of the 38th Welsh Divn were that the Denbigh soldiers would be able to communicate in Welsh with one another. There is also an appeal to the landed gentry for recruits, asking them to send their men servants to the recruiting station! I wonder how many butlers there are today around Denbigh?

The book is a worthy encapsulation of local history pertinent to WWI, and the author and his collaborators are to be congratulated on their efforts to ensure the experiences of Denbigh men and their families are properly recorded.

The book can be bought through Clwyd Wynne of the Denbigh Historical Society at the Denbigh museum.