The Dragon’s Voice

In this edition, we have two reviews of books which deal with the visual record. The first is a collection of photos in British archives, mostly the IWM. The second is a book of the paintings and drawings of the renowned war artist Fortunino Matania. So, there are lots of photos in this issue! We also have an article from Terry Jackson on the ship Peel Castle which was requisitioned for war service.

The next issue of this newsletter is likely to be in September.

For obvious reasons, we have no face to face branch meetings for the foreseeable future.

Book Review

The First World War in Focus

Rare and Unseen Photographs

Alan Wakefield

IWM, 2018

Alan Wakefield is senior curator at the Imperial War Museum and the leading light in the Salonika Campaign Society. Through his inside knowledge, he has put together a collection of photos of WWI, including the less well-known campaigns. As it is a book of photos, with some text to explain the context, this review will largely consist of photos.

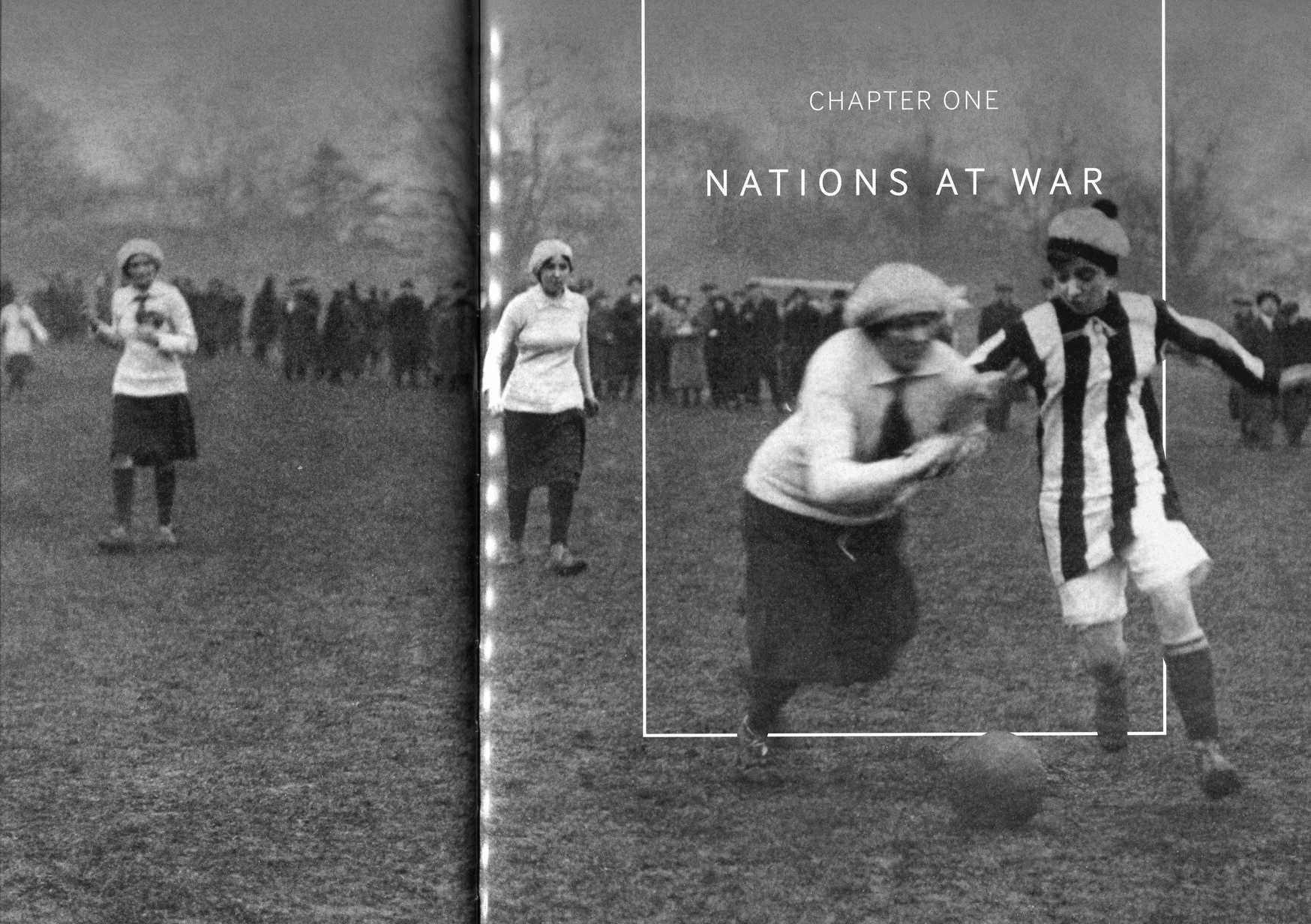

A match between two teams of munitionettes: “The Humber Girls” from Coventry in black and white stripes versus “The Vickers Girls” from Crayford.

Women’s football is nothing new! The score is not recorded but one caption states that the Humber Girls won the game. I like the hats!

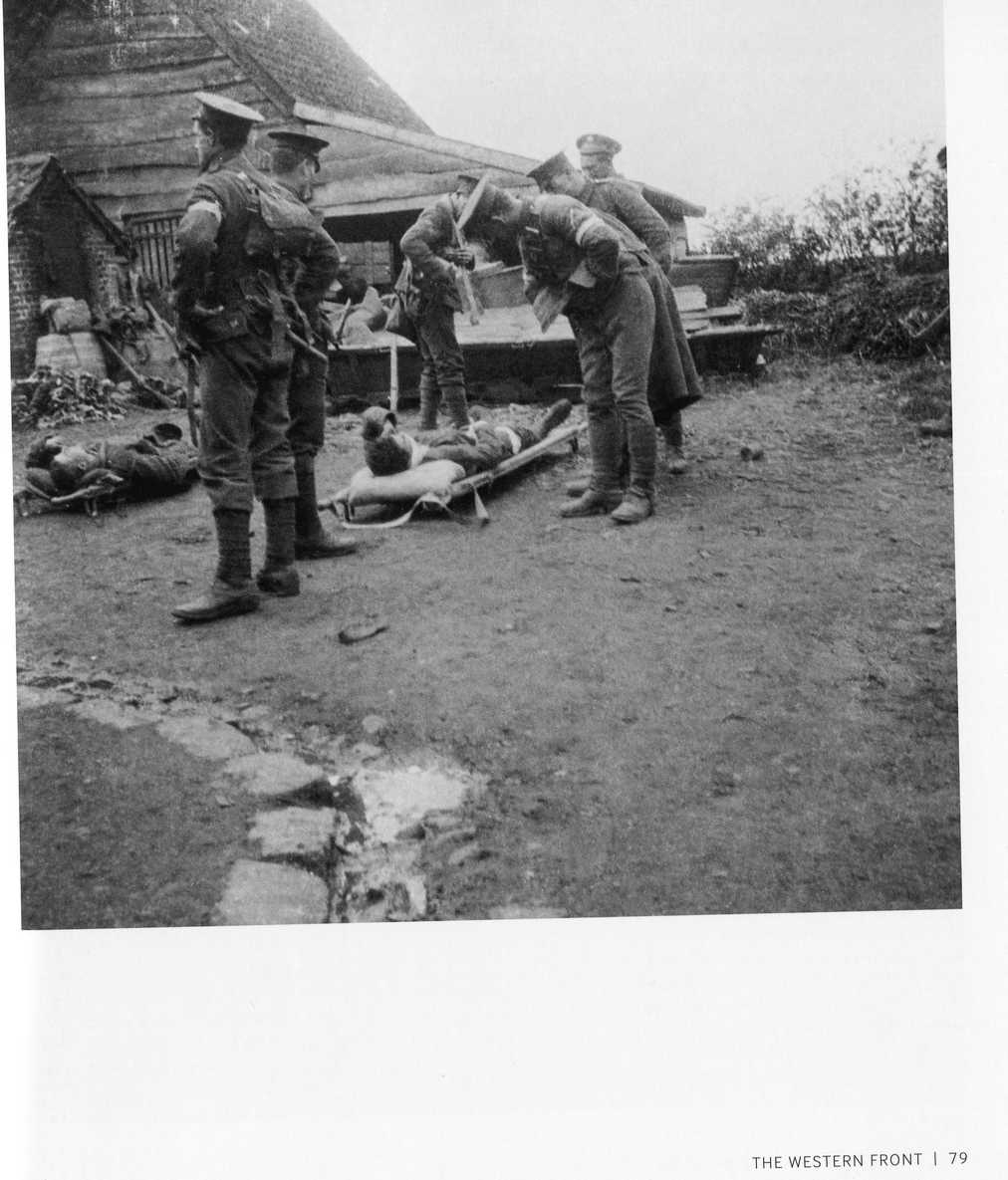

The first wounded soldiers from units of the 7th Division during the First Battle of Ypres, October 1914.

This was taken by Sergeant Christopher Pilkington, a professional photographer who accompanied the 2nd Scots Guards overseas to produce a visual record of their war service on the Western Front. He returned home in March 1915 when rules on the use of personal cameras were tightened.

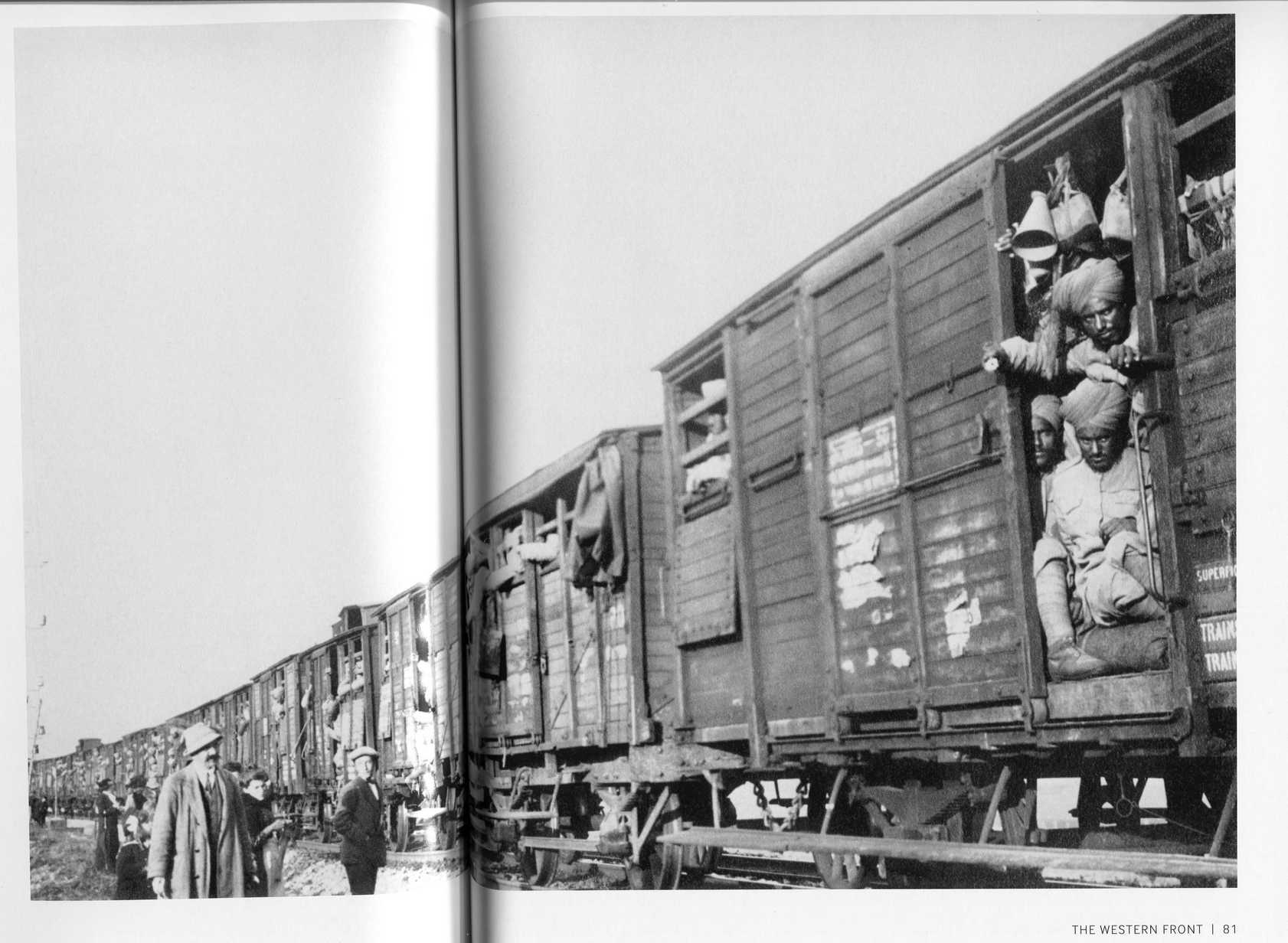

Soldiers of the 47th Sikhs on a troop train in France, October 1914, travelling to reinforce the BEF. They eventually arrived at Arques in the Pas de Calais on 20th October, and joined the 3rd Lahore Divn at Meteren.

Photo by Lt Col Coudrey.

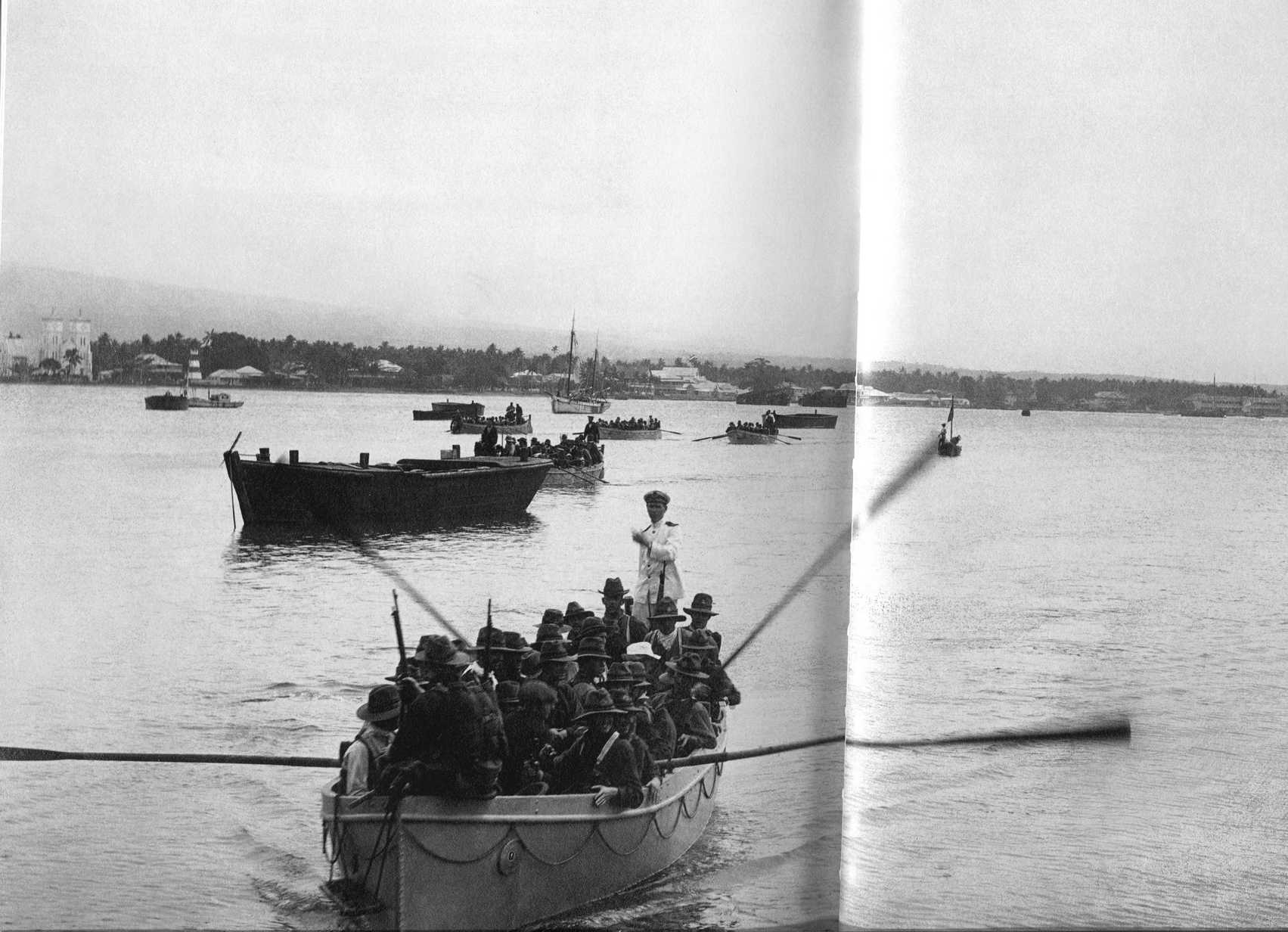

The landing of New Zealand troops at Apia in German Samoa, 29 August 1914.

The photo is one of a series taken by Alfred John Tattersall, a New Zealander who worked in Samoa between 1886 and 1951.

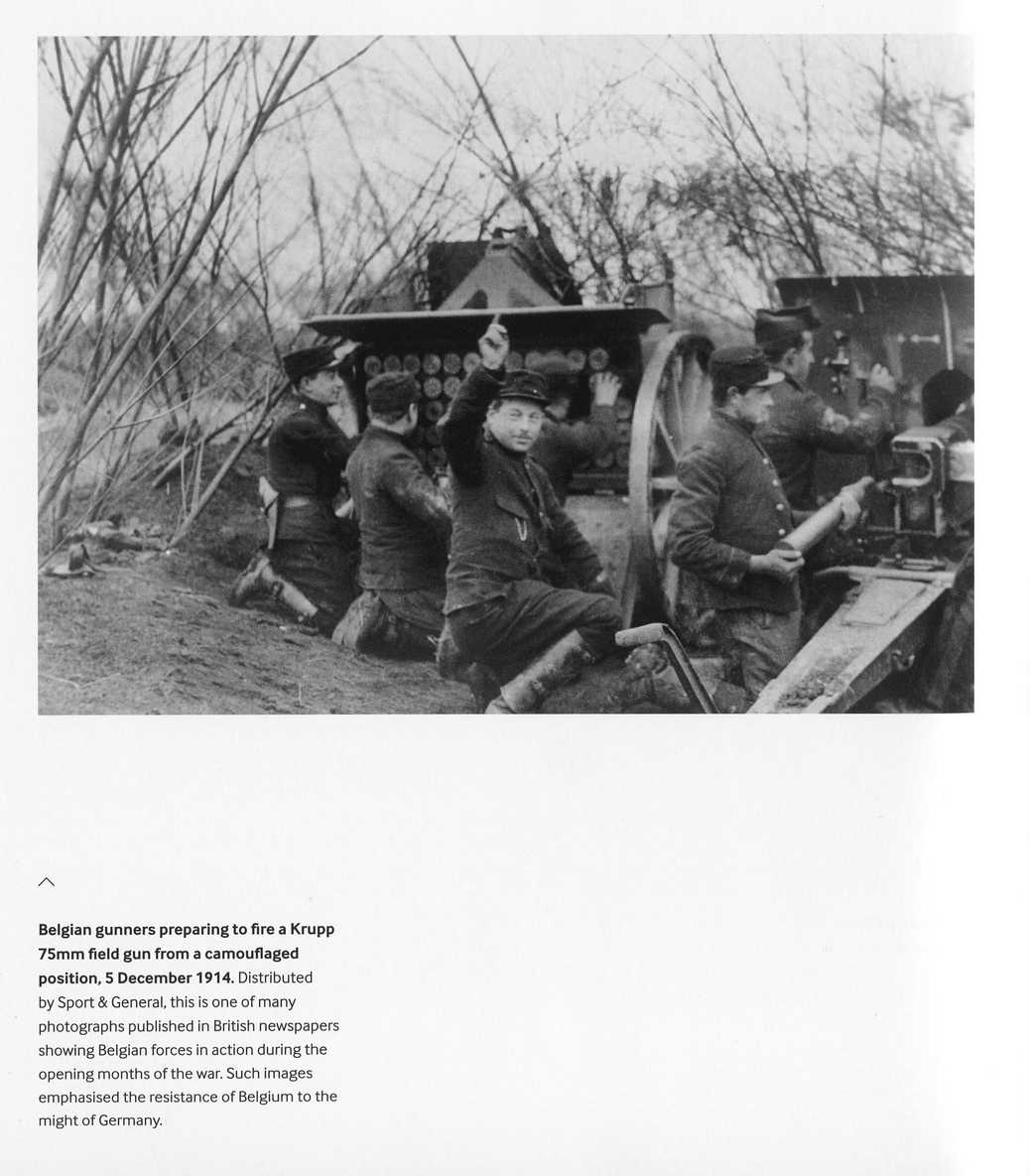

Belgian gunners preparing to fire a Krupp 75mm field gun, 5 December 1914.

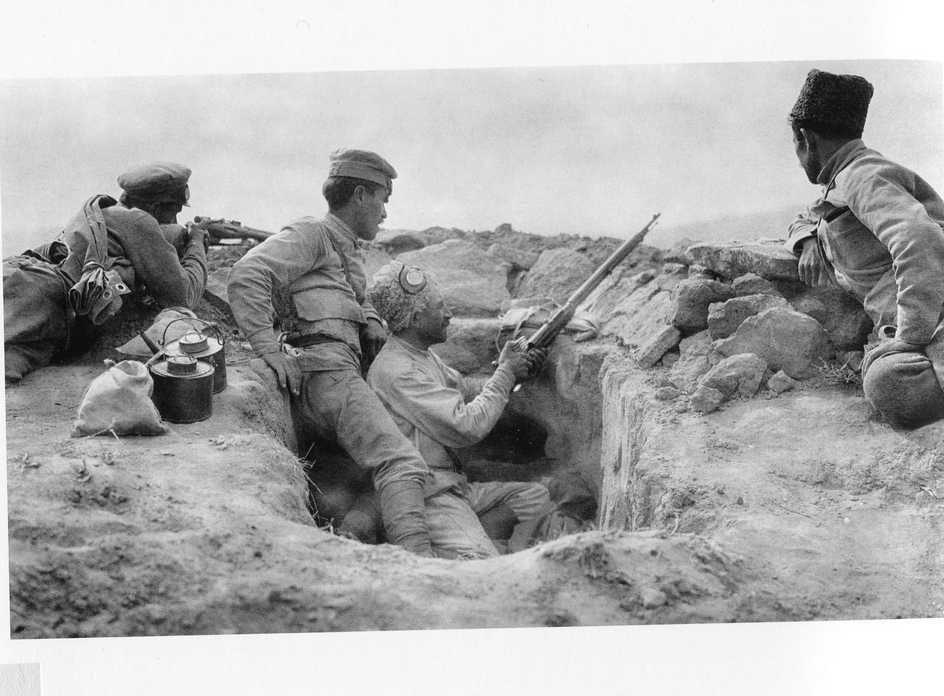

An Armenian piquet post in the hills, with soldiers on the lookout for Turkish forces.

This is one of a number of photos by Ariel Varges, documenting Armenian forces serving alongside the British in the Caucasus during 1918.

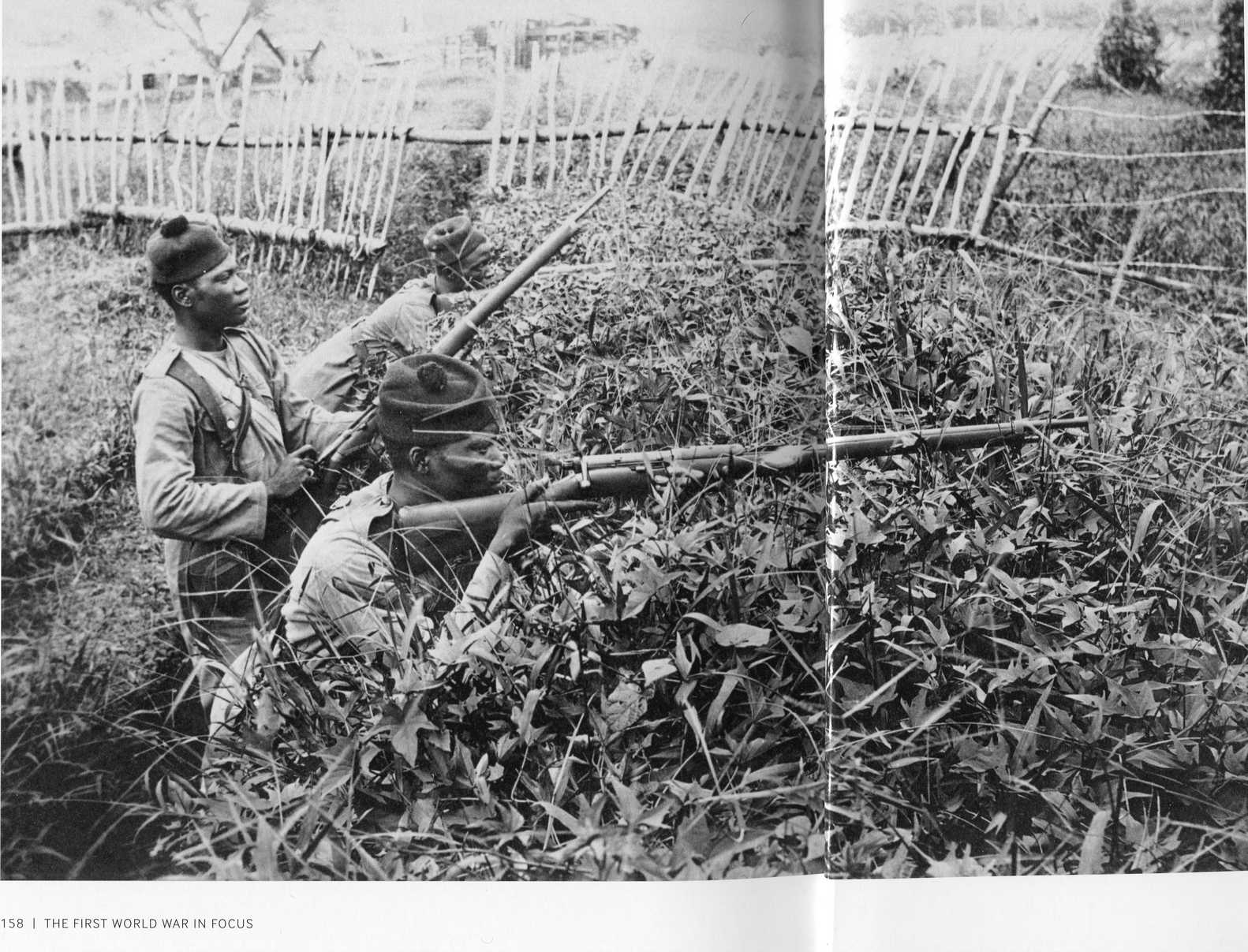

Soldiers from the 3rd Battalion, Nigeria Regiment manning a fire trench in the captured blockhouse line at Ossidinge, in the German colony of Cameroon, 1915.

This is an action in West Africa in 1915. In 1918, soldiers from Nigeria and Ghana, as they are today, also served in the East Africa campaign. Black soldiers in WWI have been ignored until very recently. Even the names of the dead were not recorded.

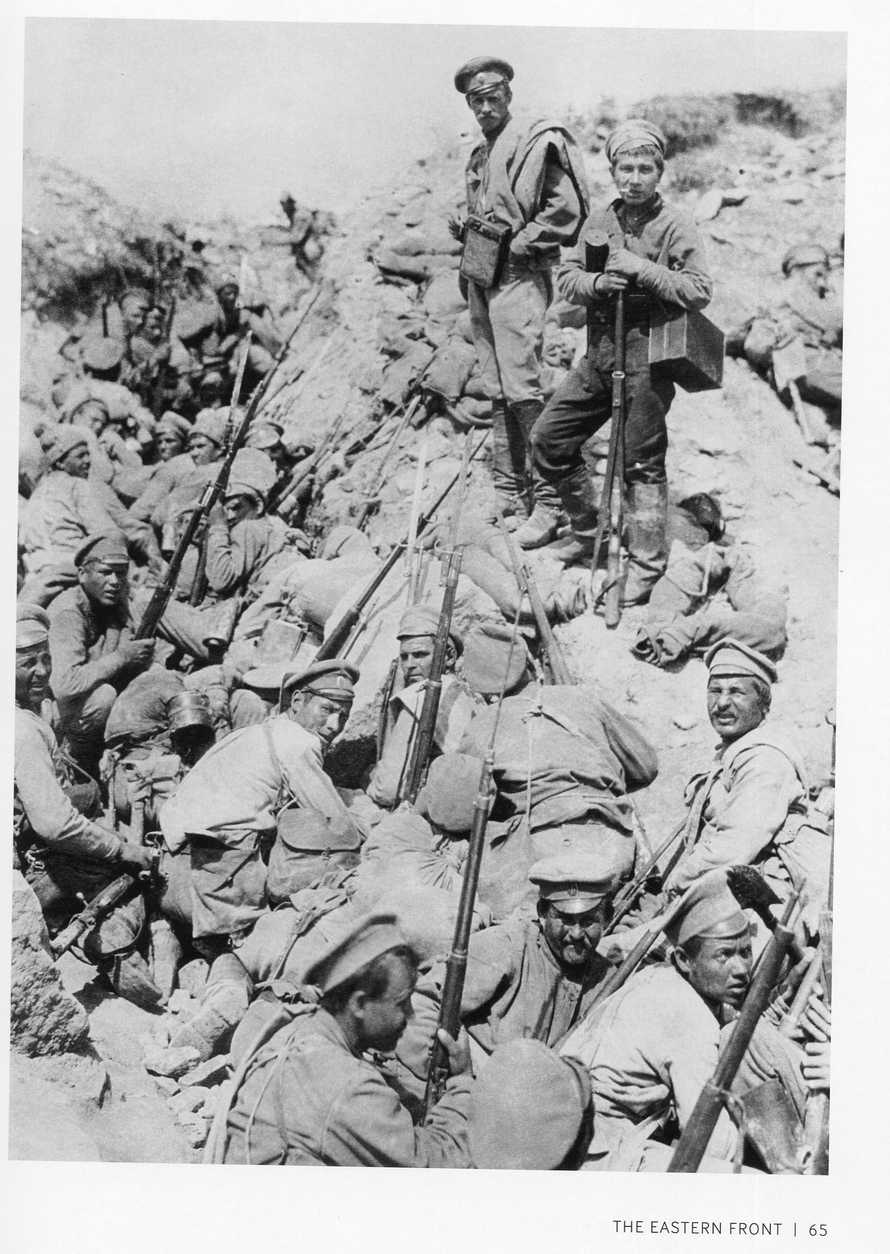

Russian soldiers. A second wave of an assault force, made up of infantry from Siberia, awaiting the order to advance agaisnt a fortified position south west of Tarnopol during the Kerensky offensive in July 1917

Louis Grondjis, a Dutch journalist travelling with the Russian army, accompanied the attacking troops and took this photograph. The officer standing on the bank is Lieutenant Glouschkoff, who was killed in action an hour later.

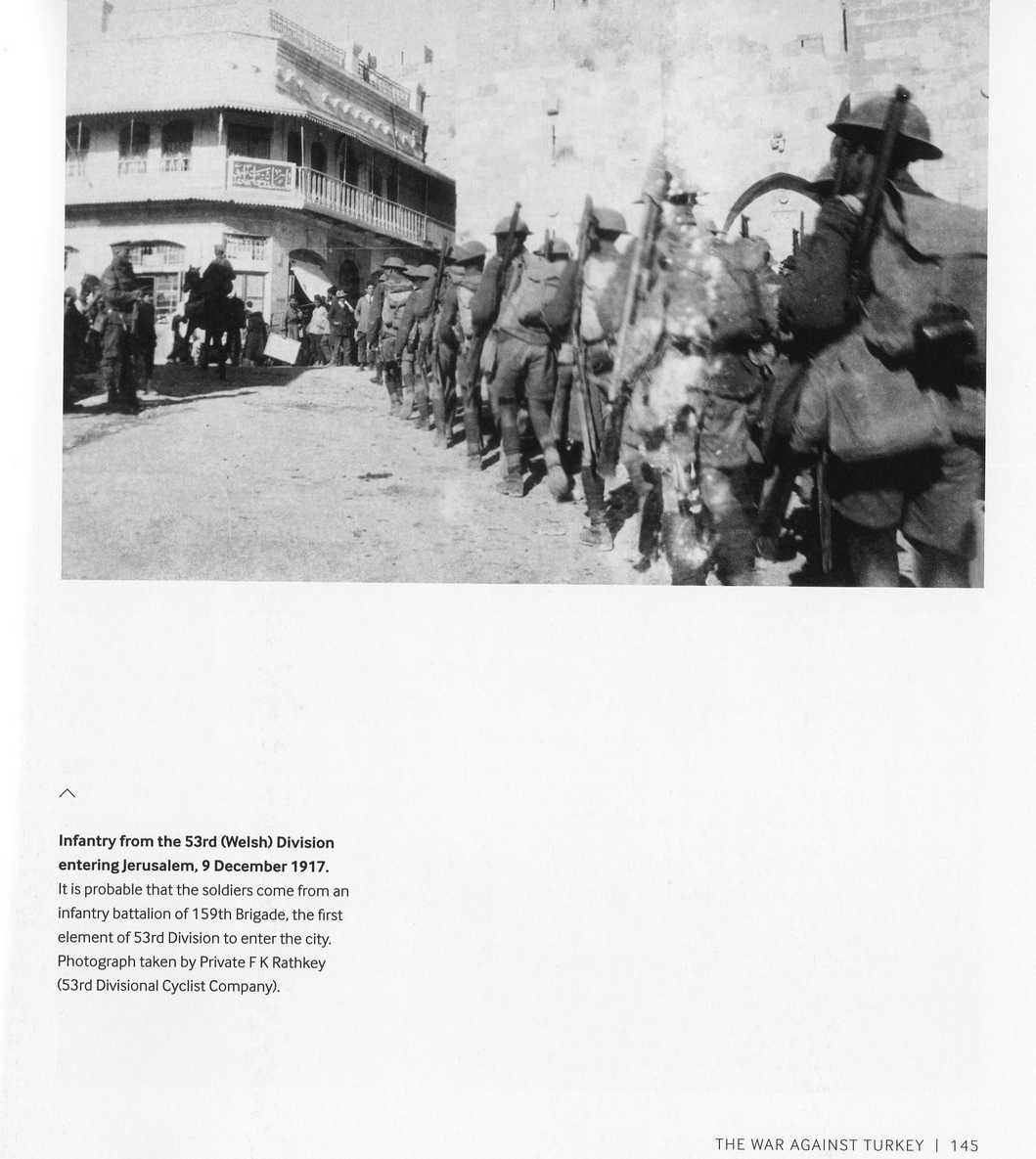

Infantry of the 53rd (Welsh) Divn entering Jerusalem, 9 December 1917

Infantry of the 53rd (Welsh) Divn entering Jerusalem, 9 December 1917

It is probable that the soldiers were from an infantry battalion of the 159th Brigade, the first element of the 53rd Divn to enter the city. Photo taken by Private FK Rathkey (53rd Divn cyclist company),

Overall, you can see from this small extract that the book is a remarkable collection of photos, including of aspects of WWI which are not well recorded. It is to be highly recommended.

Book Review

Illustrating Armageddon

Fortunino Matania and the First World War

Jim Davies

Unicorn Publishing, London, 2019

Fortunino Matania was the son of an artist and the grandfather of an artist. Art runs in the family. His WWI paintings and drawings are noted for their accuracy and authenticity. This stems from the fact that he regularly visited the Western Front and, there and in Britain, interviewed veterans and used models to get the facts right. Props which he used included weapons from the army, which he still possessed in the 1930s as he had not bothered to give them back!

Matania was Italian and never gave up his Italian citizenship, which meant he was interned in WWII. His career in England started when he was employed in 1904 as an artist by the London magazine Sphere. His war work started when he was sent by the magazine to talk to wounded soldiers at the London Hospital, Whitechapel, in September 1914, to record their recollections of the events of August 1914. He was later a designated war artist, and in 1915 was sent to the Western Front to record events. His paintings and drawings were never over-sentimentalised, though I challenge you not to have a lump in your throat when you see “Good bye, old man” which was a commission from the Blue Cross Fund, and subsequently published in The Sphere and other publications (see below). I wonder if it is where the idea for Warhorse came from? Perhaps the most memorable of his works is the Last General Absolution of the Munsters at the Rue du Bois. It is used for the cover of the book.

I have to declare myself as an undiluted fan of Matania’s work, a small selection of which is reproduced below. The book runs to 416 pages and is the only record of all of Matania’s WWI work. I have to say that the fly in the ointment is that most of the paintings are only reproduced in the book as black and white photographs, not colour. I presume this was done on cost grounds but it does seem to be a mistake. Maybe there will be a second edition in full colour? Where a date is given, it is the date on which the painting or drawing was made, not the date of the event depicted.

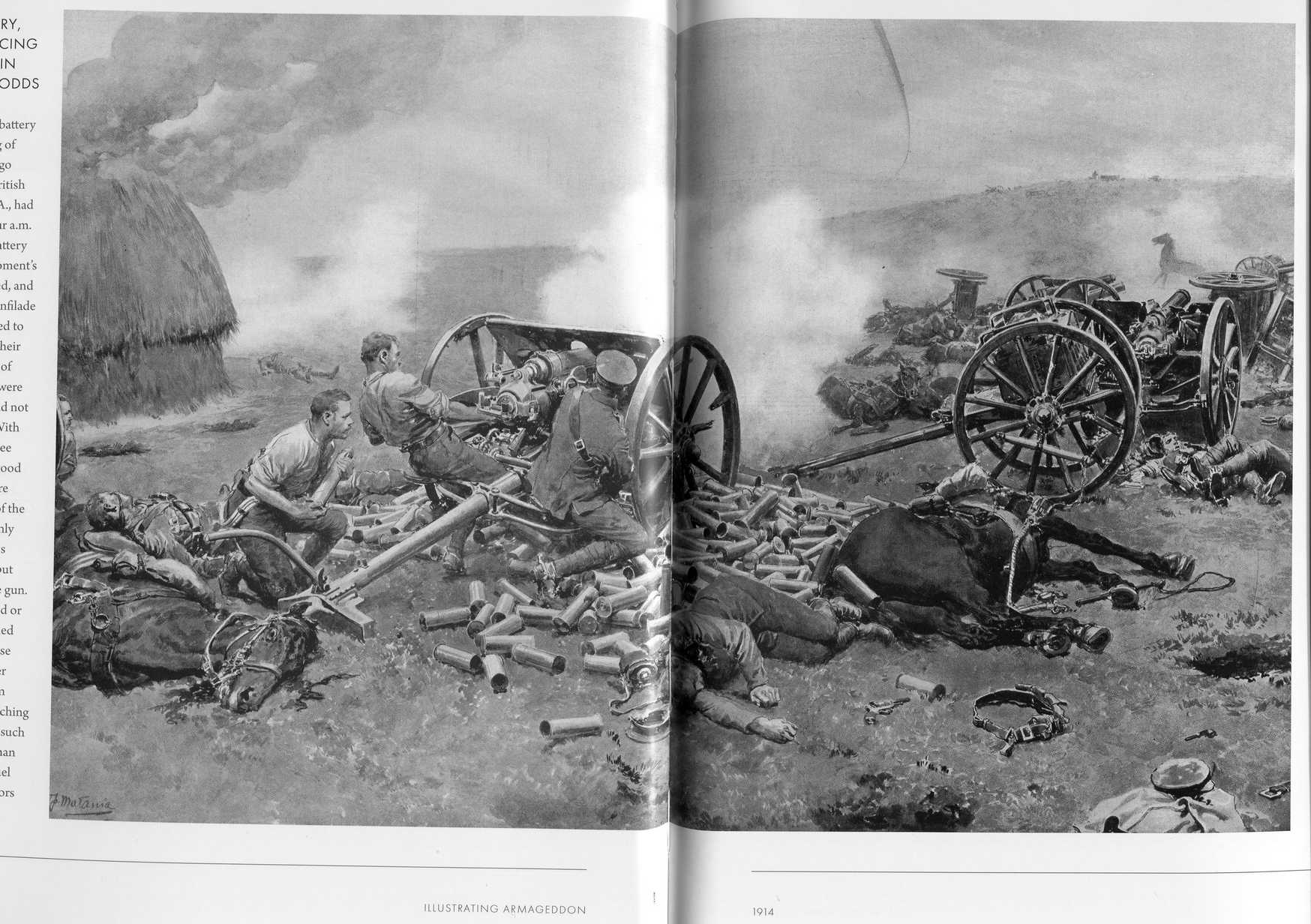

Three survivors of L battery, Royal Horse Artillery, silencing the fire of the enemy guns in the face of overwhelming odds.

This was the Affair at Néry, 1st September 1914, on the retreat of the BEF from Mons, when the single remaining gun continued firing when their other guns had been knocked out. Three members of L battery were awarded the VC for this action.

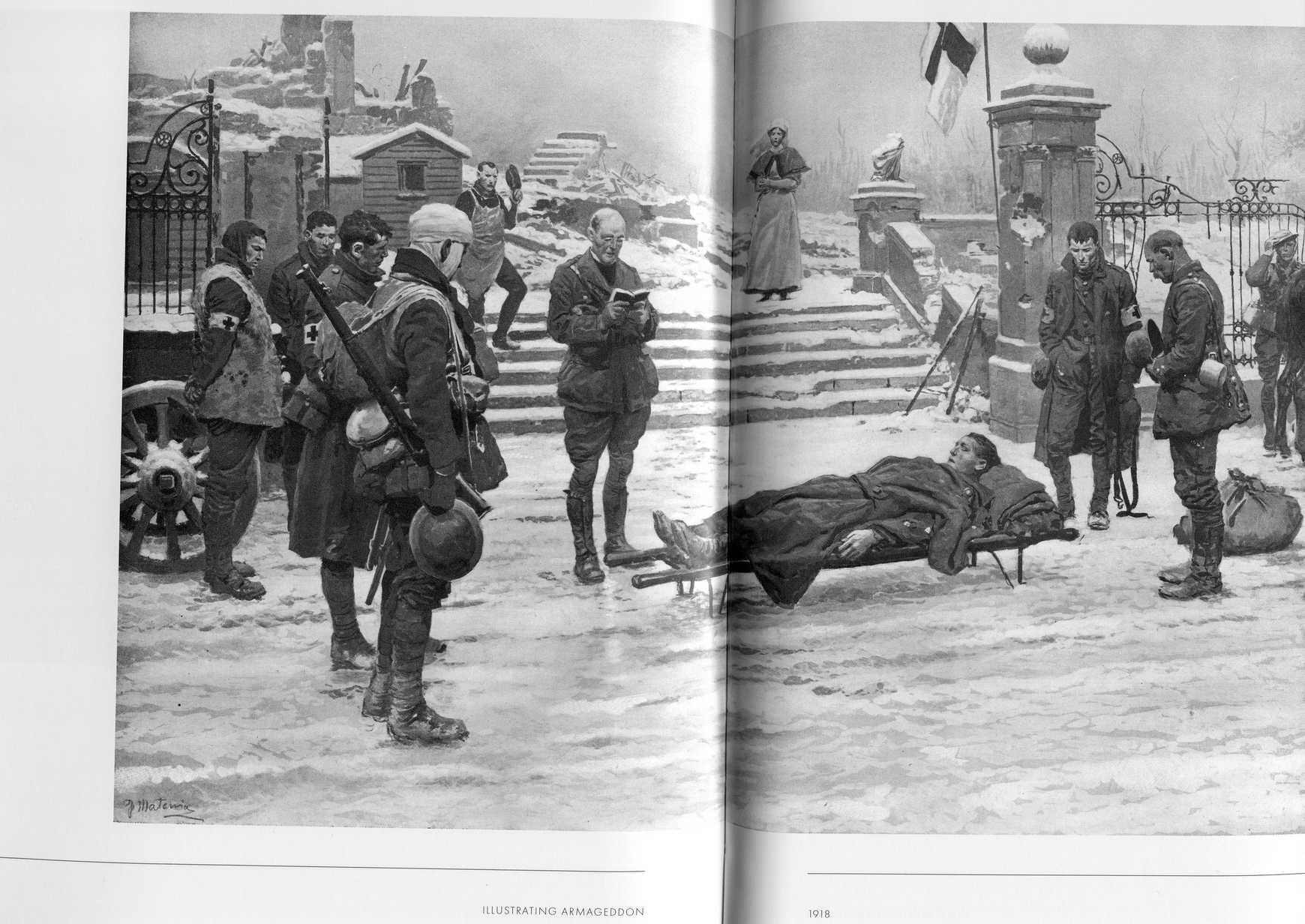

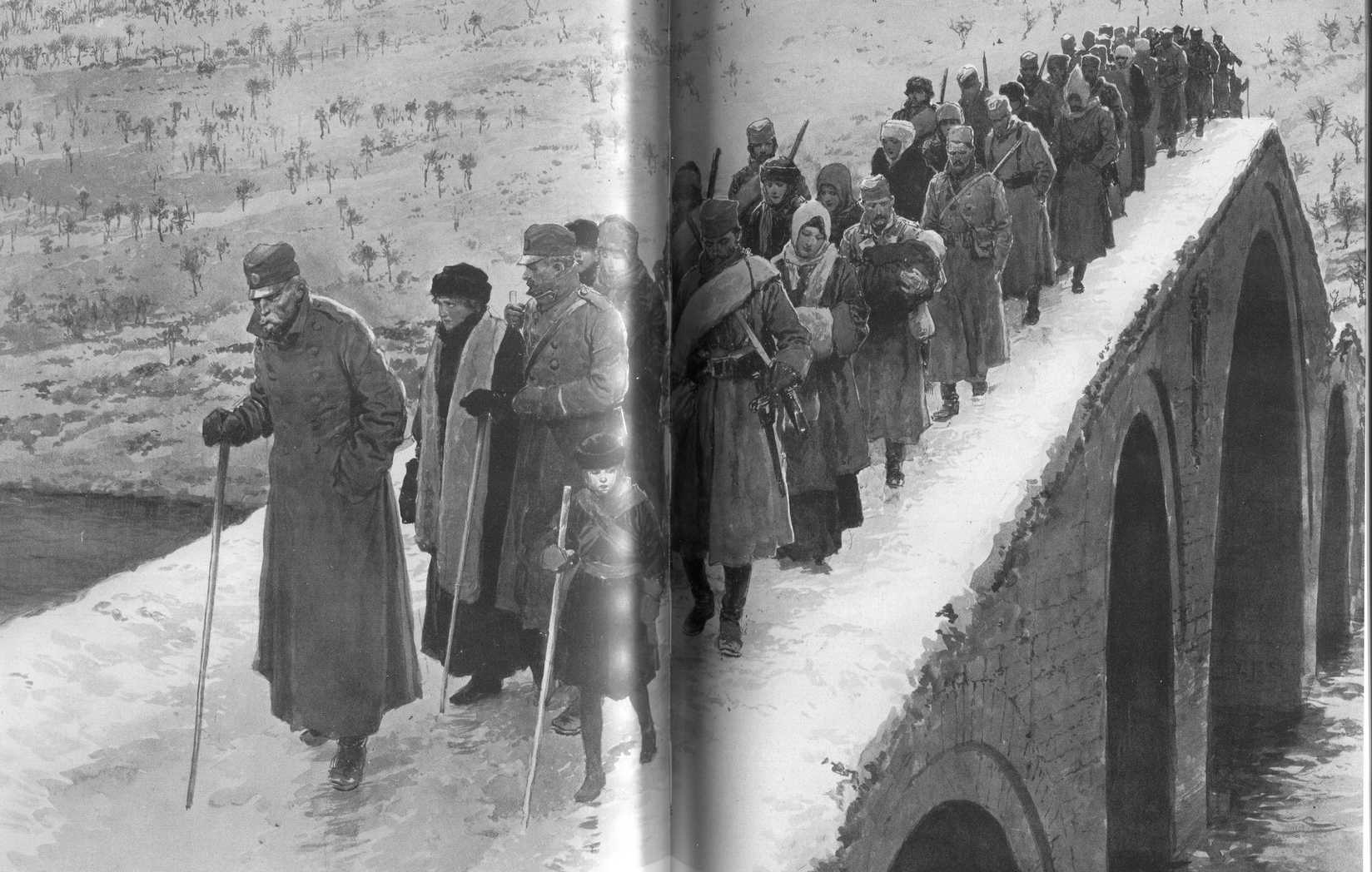

The Passing of a Hero.

King Peter, accompanied by his court and by a detachment of Serbian soldiers, leading the way during the retreat from Serbia, across the mountains into Albania. January 22nd, 1916.

Following their defeat, the Serbian court had to endure the same hardships as the rest of the Serbian refugees, trekking over the mountains into Albania. The painting is based on official Serbian photos of the retreat.

The Last Message – if you get through, tell my mum. November 26, 1917.

This is one of the few paintings that is also reproduced in colour. I wonder if the writers of the film 1917 had this painting in mind when they wrote their script.

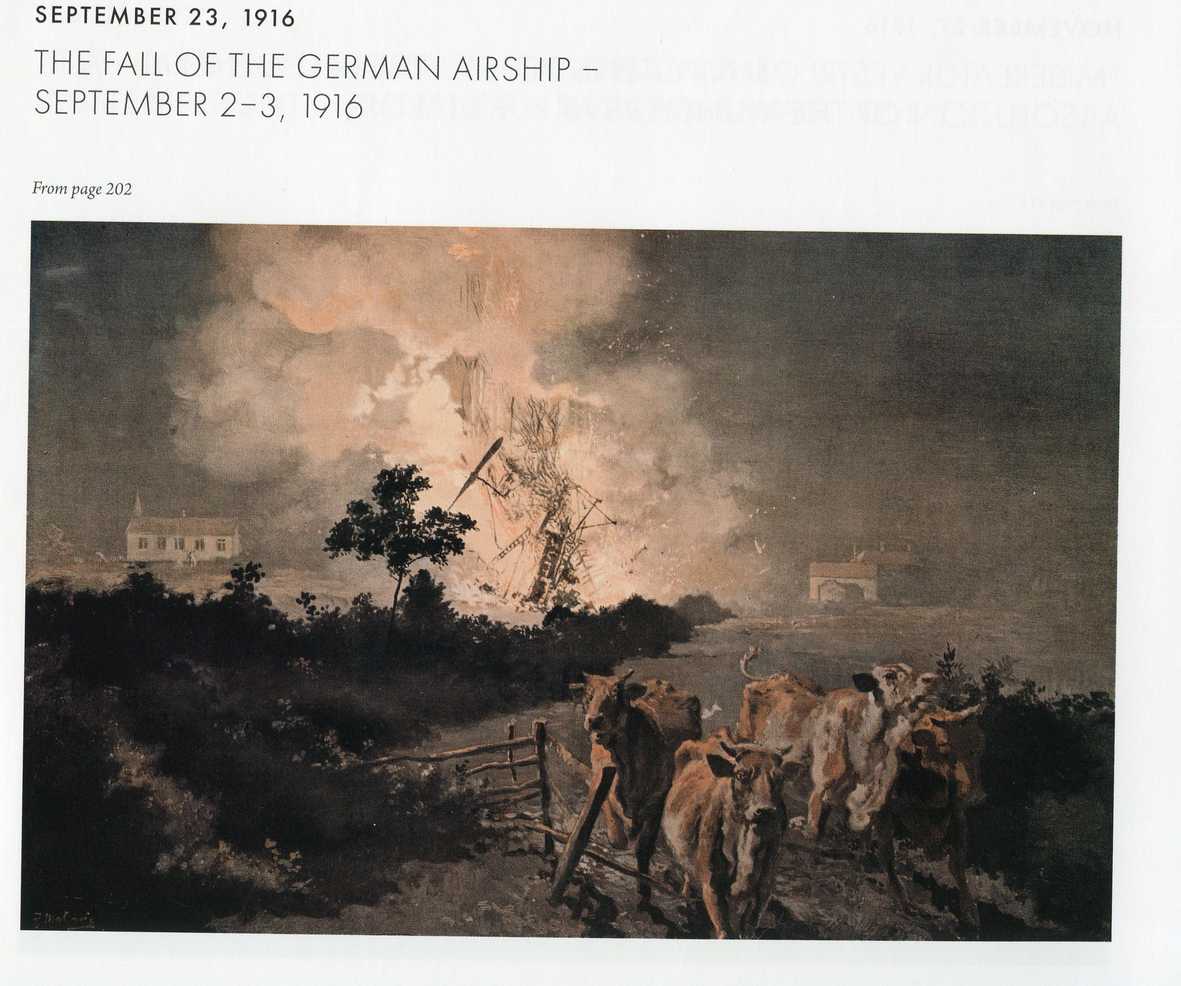

The Fall of a German Airship. September 23 1916.

Matania was close by when the airship was shot down near Cuffley in Hertfordshire.

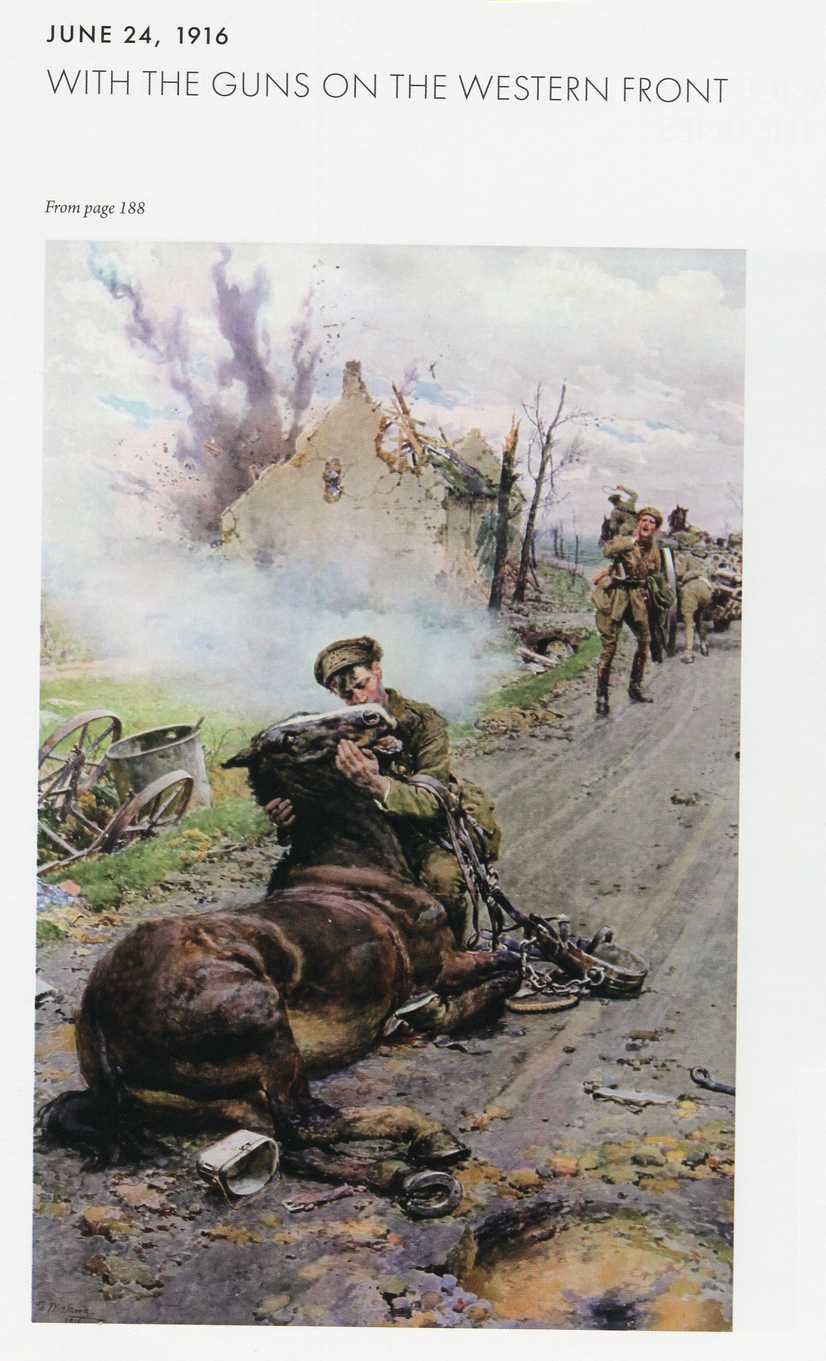

Goodbye, old man. June 24 1916.

An incident on the road to a battery position in Southern Flanders. A gunner says farewell to his wounded horse, as his comrades urge him to come on. This was a commission from the animal charity Blue Cross Fund, and was sold as a print into the 1930s. Is there a dry eye in the house? Indeed, did the writers of War Horse draw inspiration from this painting?

And finally:

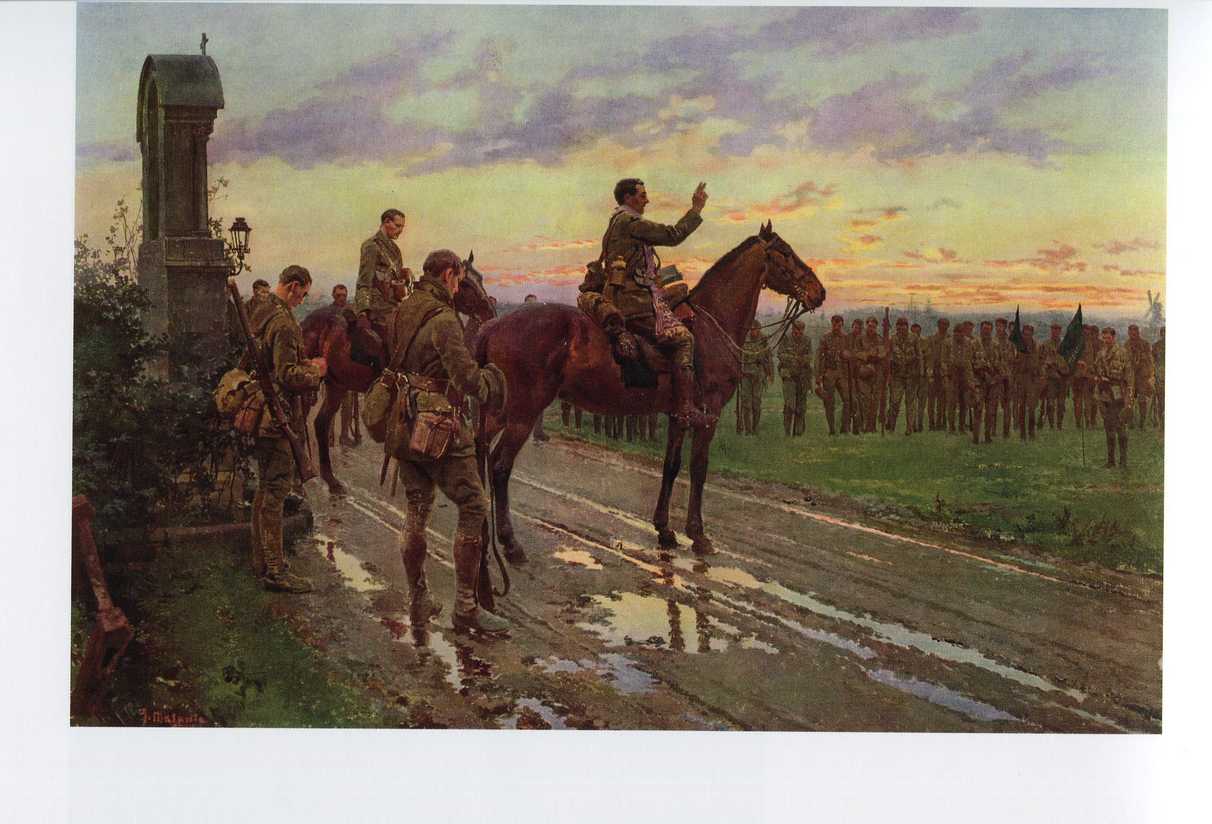

The Last General Absolution of the Munsters at Rue du Bois. November 27, 1916.

This illustrates a scene on May 8, 1915 when the 2nd Royal Munster Fusiliers were on their way to take their place in the trenches at Rue du Bois, at Neuve Chapelle. At a broken roadside shrine, Colonel Rickard formed the men up in three sides of a square, and Father Gleeson gave a general absolution. He survived the war and returned to Dublin where our good friend in the Dublin WFA, Sean Connelly, can remember him as a red-faced elderly priest who got rather annoyed by the little boys of the locality. Father Gleeson’s WWI diaries have survived and are in the library of University College Dublin.

The Peel Castle on War Duty

Terry Jackson

During the early stages of the War, the Admiralty found it necessary to have auxiliary ships fast enough to overtake merchantmen and large enough to accommodate sufficient men to form boarding parties and prize crews.

When the Peel Castle was still engaged on the Liverpool and Douglas service, a naval constructor came from London to examine the ship. On his recommendation, it was chartered on the completion of the summer service. Five weeks fitting out was done by Cammell Lairds of Birkenhead. Accommodation was made for one hundred officers and crew, the military and navigating duties being undertaken by Royal Naval and Royal Naval Reserve men. The engine department was staffed mostly by employees of the IOM Steam Packet Company. Peel Castle was commissioned on 14 November 1914, under the command of Lieut-Commander PE Haynes, RNR, an officer with considerable naval experience, who had been in the service of the P & O Company for many years.

Upon completion, the ship sailed under sealed orders from Birkenhead on 22 November 1914. After undergoing gun trials in the Channel, she proceeded to sea. It was the first ship of this class to sail from Liverpool. After sea trials she arrived at Scapa Flow on 24 November and after coaling, proceeded to Plymouth for repairs to damage caused by the rough weather. She then continued to the Downs to patrol from January 1915, to February 1916.

The Dover Straits had been closed by our mine-fields and anti-submarine nets. All vessels bound for Continental ports were examined before being allowed to proceed. Peel Castle became attached to the Downs Boarding Flotilla, a section of the Dover Patrol under Admiral Bacon. The narrow stretch of water extending between the Goodwin Sands and the Kentish coast at this time was the busiest spot on our coasts for shipping.

This was a huge undertaking. During a period of six months, 21,000 merchant vessels passed through the Patrol, an average of 115 vessels per day. The work of the patrol boats was carried out meticulously and only four per cent were sunk, with a loss of seventy-seven officers and men. Her duties consisted of regulating traffic, examining neutral ships for enemies and contraband and as a guard ship in the Downs. She would spend ten days at sea, then four in Dover port for restocking.

Her first job was to stop a Greek ship trying to slip away in the dark. Soon after, she fired at a large ship flying the Red Ensign that failed to stop whilst passing through the Downs. The ship then fired at Peel Castle from a large calibre weapon, so it was left to more appropriately armed vessels to give chase.

The Peel Castle in dazzle camouflage

The Admiralty had information that Germans were returning home as stowaways in bunkers of neutral ships, so she was ordered to send an engineer officer and a party of stokers to search the engine-rooms and bunkers of neutral vessels, especially those of ships hailing from United States ports. On 1 May 1915, a Douglas engineer and a party of stokers were searching a Dutch ship whose engine-room staff were mustered together in the engine-room. One of the stokers going through a coal bunker was surprised to see a pair of eyes staring at him from behind a heap of coal. He quickly got out and returned with the engineer. They discovered a stowaway, who was taken prisoner. On interrogation on the Peel Castle, he was proved to be a prominent New York business man. He was promptly sent ashore and interned. As he was the first stowaway to be captured, the crew were congratulated on their vigilance. At this time, American newspapers often found on stowaways were more conciliatory to the enemy.

One of Peel Castle’s interpreters was a Belgian, formerly in the service of the Antwerp Harbour Board. He could spot a German immediately and could tell from which part of Germany he came by his dialect. On 11 June 1915 an engineer and search-party examining the Dutch steamer Rotterdam captured the second engineer of the German cruiser Prinz Eitel Frederick on the Dutch ship. He was disguised as a greaser. His ship at that time was interned in a United States port.

On another occasion, while searching a Holland-American ship from New York, they captured two German prisoners who were kept on board the Peel Castle and examined by the senior naval officer of the base. One of them proved to be the notorious Franz von Rintelen, one of Admiral Tirpitz’s special spies and the man who organised the bombing campaign in the United States against Great Britain, setting fire to factories and placing bombs in ships. The other man claimed to be a railway magnate from Mexico, but he turned out to be von Rintelen’s chief assistant. They were promptly imprisoned and were finally deported to the United States for trial.

The ship continued on patrol engaged in various activities until on 7 February 1916 disaster struck. At 1 am, a fire broke out in a room above the magazine. Despite using all the fire hoses, the fire spread and it was necessary to flood the magazine. At this time, it was realised that Mr Steele, one of the interpreters, was missing. Fortunately, the wind was light and it was possible to lower the lifeboats as a precaution. Thirty men remained on board to work the hoses and pumps. The remainder boarded the lifeboats. Meanwhile the tug, Lady Brassey, came alongside with her hoses, which appeared to contain the fire. However, at 3 am, the amidships caught fire and ammunition by the guns began to explode, causing the ship to be abandoned. Eventually, the tug got a tow rope onto Peel Castle and towed the ship to shallow water where it would not block the passage of other vessels.

The crew were eventually taken to HMS Louvain. The next day, the Captain and some men returned to their ship and put out the smouldering fire. Unfortunately, they found the remains of Mr Steele. On 13 February, Peel Castle was towed to Chatham Dockyard for a refit. It took six weeks to put Peel Castle once more into condition for further work. On 9 August 1916, she went back to her old job in the Downs. Things there were then quite lively. German submarines were very active and Peel Castle had to take over the crews of two ships which had been torpedoed. Meanwhile, German aeroplanes dropped bombs on Dover and Deal.

Subsequently, the ship was ordered to engage as an escort for the Norwegian convoys. This was somewhat disconcerting as an earlier convoy had been completely destroyed by German cruisers and Commander Haynes was also promoted to Captain RNR in charge of the Atlantic convoy. She was fitted out for her new task at Leith to enable the use of depth charges and anti-mine paravanes.

Her patrol area was between the Orkneys and Shetland Islands, a favourite route for enemy submarines heading for the Atlantic. Subsequently she was sent to protect the Humber-Tyne Convoys. The deep water between Flamborough Head and the Tyne was ideal for submarines and the enemy had much success, so a new channel had to be swept through the minefield.

Convoys ranged from thirty to sixty ships, sometimes as slow as seven knots and were escorted by a destroyer. Peel Castle kept observation on the seaward side at fourteen knots going up and down the convoy.

On the day after the Armistice, the ship took a final convoy south and docked at Immingham until the end of December, when it returned to the Downs. She then passed Dover and suffered two days in the Channel in a heavy gale that washed away her forward anti-aircraft gun, eventually arriving in Liverpool on 4 January 1919, where the crew were paid off. She still had some work to do. She was fitted out at Birkenhead to bring home troops from the Western Front. She worked from Southampton until May, when she was refitted at Liverpool to resume her original work for the IOM Steam Packet Company.