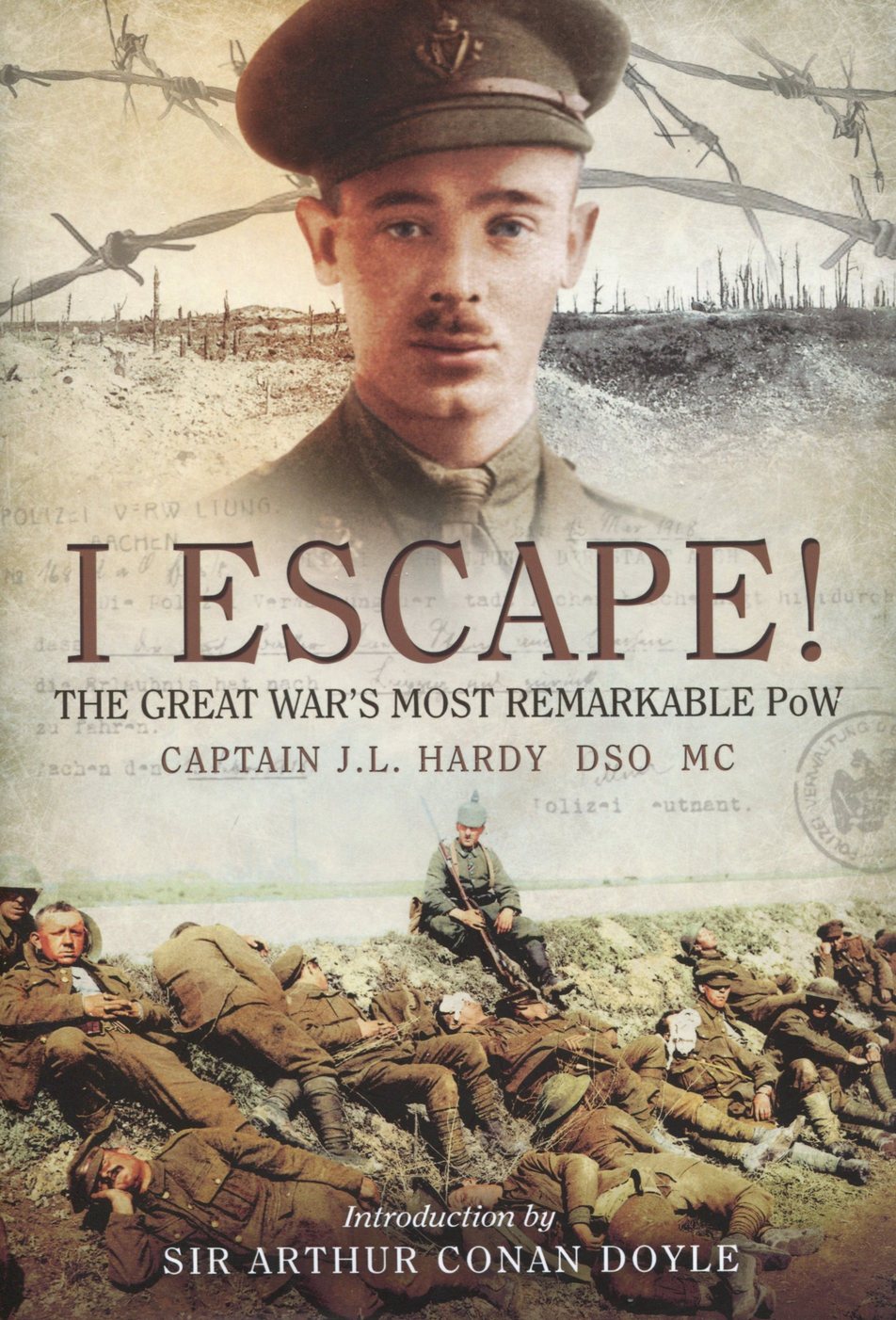

I ESCAPE!

The Great War’s Most Remarkable PoW

Captain JS Hardy DSO MC

Introduction by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Pen & Sword Military, Barnsley

2014, £19.99, xvii, 158pp, ills

ISBN 978-1-47382-376-1

This book was originally published in 1927, hence the original forward by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Jocelyn Lee Hardy had a somewhat chequered career, as we will see, and a varied life. He had some family connections with Ireland as his father was from County Down, and so joined the Connaught Rangers, much like Max Staniforth did, and was later in the Inniskillings. After the Great War, Hardy was in Dublin probably as part of the notorious “Cairo gang”, who were a section of British intelligence.

This book is an account of Hardy’s escape exploits as a PoW in Germany. After many fruitless attempts, he did in fact succeed in getting across the Dutch border, and returned to active service right at the end of the war, before being invalided out with a severe wound that resulted in the loss of a leg. It is worth noting that this book, of course, predates both the popular image of WWII escapees in films and books, and, of course, the Colditz book by Airey Neave “They Have Their Exits”, also incidentally recently republished by the same publisher. In the Great War, there were most certainly PoW camps and would-be escapees, and Hardy was one of those!

Hardy’s war finished for the first time when he was captured on 27th August, 1914 at Maroilles as part of the action at Le Grand Fayt, and he then spent over 3 years as a prisoner in Germany. His final, successful, escape attempt was remarkably undertaken from Fort Zorndorf which was the furthest location from the Dutch frontier of any of the camps that he was in. In fact, the camp was almost on the Polish border and was the equivalent of Colditz Castle in WWII, that is, a very secure camp for troublesome escapees. It is quite remarkable how far he got across country in his adventures as he covered quite a lot of ground in Germany, mostly by train. Of course, he spoke good German and French. Is there a lesson there for language teaching in our schools today, and even for WWI historians who complain about sources not being in English?

The book is written in an easy to read, newspaper style. I can only describe it as a cross between the, serious, Colditz memoirs of Airey Neave and Michael Palin’s, fictitious, “Ripping Yarns”, if you are old enough to remember them. It is excellent that it has been republished and the publisher is to be congratulated for doing so.

Hardy became very good friends with a Russian officer, Baschwitz, with whom he had a long but ultimately unsuccessful journey round the Baltic coast. Remarkably, in their travels Baschwitz called on a German family whom he knew in Berlin to see if they could help him, but unfortunately the husband was away. Nonetheless, the wife gave him a handful of her husband’s cigars and did not call the police. Although this particular odyssey ended in failure when the two escapees were recaptured on the island of Rugen, Baschwitz did later manage to escape to Britain. Hardy and Baschwitz met up when they were both back “home” and there is a photo of the two of them together on the back dust cover. Incidentally, Baschwitz spoke impeccable English, French, and German to the extent that he could argue with German officials and not be spotted as a foreigner. Whow!

Amongst the other prisoners that Hardy mentions is Roland Garros, the French air hero, who also escaped successfully in 1918 from Zorndorf, but was shot down and killed just before the end of the war in the Ardennes. The French tennis stadium and tournament are named after him, as he was a keen tennis player when he was a student in Paris.

The preface to the re-published version of the book does, to its considerable credit, deal with Hardy’s time in Dublin during the Irish War of Independence, which was far from being Britain’s finest hour. In 1920, Hardy was implicated in the deaths of three republican prisoners who were supposedly “shot while trying to escape”, as retaliation for the assassinations earlier that day of some of the Cairo gang, who were British intelligence officers and who, unbelievably, lived in digs in middle-class civilian Dublin. The assassinations were followed later that day by the British Army firing into the crowd at a Gaelic football cup final and killing, at random, 14 civilians as retaliation. This day was referred to as the original “Bloody Sunday” as 31 people are believed to have died.

Hardy was not in the Black and Tans, who never operated in Dublin, nor does he seem to have been in the “Auxies” who did operate there, but rather seems to have been in military intelligence of some sort. He is believed to have killed the grandfather of the actor Brendan O’Carroll in his own home in central Dublin, as described in a recent episode of the BBC’s “Who Do You Think You Are”, available on DVD. Hardy later became an affluent banker, drove a Rolls Royce and wrote some works of fiction. So, as I said earlier, a rather chequered career! Indeed, one cannot help but wonder what effect 3 years of captivity and then being back in the carnage on the Western Front had on his mental state.

All in all, this does not detract from the book on his escape activities but perhaps helps to place his life into some sort of perspective. I would happily spend my own money on the book.

Trevor Adams